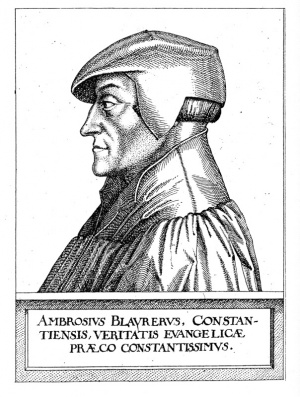

Blaurer, Ambrosius (1492-1564)

Ambrosius Blaurer (also Blarer or Blaarer), Swabian reformer, b. 12 April 1492 in Konstanz, d. 6 December 1564 in Winterthur. In 1510 he entered the Benedictine monastery at Alpirsbach near Oberndorf. When Ambrosius Blaurer became acquainted with Luther's writings through his brother Thomas, a law student in Wittenberg, he accepted the Protestant doctrine, resigned his office as prior of the monastery, and retired to his parental home in Konstanz, remaining in seclusion until the council of Konstanz called him to the Protestant ministry on 25 February 1525. In the following year the Catholic bishop and clergy withdrew from the city.

From Konstanz as a center Blaurer aided in bringing about the Reformation in various Swabian cities, giving his special attention to the suppression of the Anabaptists. He sought with all his strength to secure the unity of the church and to fetter every deviation. In contrast to the Saxon and Swiss reformers he opposed the use of capital punishment in religious matters. He emphasized indoctrination; where this failed he advocated compulsion. Capito wrote him on 13 September 1528, that there were among the Anabaptists some pious souls, whom Blaurer could, with his gentleness, convert. But most of them, Blaurer says, were maliciously intent upon re-establishing the Mosaic law. In the city of Memmingen, which had often called upon him for advice, he secured the passage of a resolution on 9 December 1529, demanding the expulsion of Anabaptists who refused to accept the teaching of the preachers (Schiess I, 18).

In the other cities he apparently met some opposition to this policy; for the Memmingen Resolutions of 1 March 1531, passed by the Upper German cities (Biberach, Isny, Konstanz, Lindau, Memmingen, and Ulm) which had joined the Smalkaldian League, rejected violent proceedings against the Anabaptists; Blaurer presided at this meeting and was also given the assignment of drawing up the resolutions. Regarding the Anabaptists the resolutions stated that faith should not be spread abroad in the world by the use of the sword or force but by the sword of the mighty Word of God; force had only brought a larger following and greater respect to the Anabaptists. Only those persons should be expelled who spread error, instigated mob action, and refused the oath and military service (Pressel, 169, 182).

Blaurer seems to have come into personal contact with the Anabaptists for the first time when he was called to Esslingen at the end of September 1531. In this city there had been a group of Anabaptists since about 1527, which had been ruthlessly persecuted by the city council before the introduction of the Reformation; many of its members had been martyred. Blaurer did not recognize the right of this evangelical group to do pastoral work. The Anabaptists had to adhere and be subject to him. In a letter to Martin Bucer in Strasbourg, written soon after his arrival, he complained "that the evil of the Anabaptists, which has firmly imbedded itself here, will not easily be uprooted" (Pressel, 204). But he soon had to admit that the Anabaptists were not criminals, but had a genuine longing for God's Word. His simple manner of preaching directly to the heart won him their confidence. They were attracted to him by the determination with which he, like them, insisted upon religious earnestness and moral purity of life. This he soon discovered. Two months later, 27 November 1531, he wrote to Bucer, "I treat the Anabaptists in such a way that they love me and attend my sermons regularly and attentively; most of them have desisted from their error; the rest, of whom there are very few, will presumably do the same" (Schiess I, 292). He expressed himself similarly on 23 December 1531 (Schiess I, 304), and on 2 February 1532 (Schiess I, 321).

Early in June 1532, after Blaurer's return to Konstanz, a bitter quarrel arose in Esslingen among the clergy, which alienated the Anabaptists. Church discipline as introduced by Blaurer was no longer exercised; the life of many members was offensive. These unedifying conditions caused the Anabaptists to leave the church and again hold their own religious services. Blaurer was unable to pardon this step. The unity of the church seemed threatened by their separation. "More and more I hate," he wrote to his brother Thomas, 11 January 1533, "this harmful sect, which is ruinous to the unity of the church, although or precisely because they are apparently so pious and innocent. Nevertheless we are also very guilty, because we do not insist on true repentance. The unlovely conduct of so many Protestant cities takes all the pleasure out of my work and life, and I fear serious punishment" (Schiess I, 379).

After his call to the university of Tübingen (1534) we hear little more about Blaurer's steps in opposing the Anabaptists. In Tübingen he drew up an official opinion concerning the punishment of the Anabaptists, at the request of Duke Ulrich, which was presented to Philipp of Hesse on 7 June 1536 in the name of the theological faculty. Referring to the Old Testament and Augustine he granted the government the right to punish them even with death. But he warned against acting rashly, for some were merely followers. Those who refused to recant could be suitably punished by a prison sentence on bread and water. The preachers of the state church should frequently visit them in the hope of converting them (Hochhut).

The hymnbook published by Blaurer between 1545 and 1548, Ein gmein Gsangbüchle, contains songs written by Anabaptists—Dachser, Grünewald, Haetzer, and Hut (Spitta). In 1538 he had to leave Württemberg and in 1548 he had to flee from Konstanz; the rest of his life was spent as preacher in Winterthur and Biel (Switzerland).

Bibliography

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. I, 226.

Hochhuth, Karl Wilhelm Hermann. Zeitschrift für historische Theologie 28 (1858): 566, 586-591.

Hottinger, Johann Jakob. Helvetische Kirchen-Geschichten, vorstellende der Helveteren ehemaliges Heidenthum und durch die Gnad Gottes gefolgetes Christenthum ... Zürich: Bodmer, 1708: III, 439.

Keim, Karl Theodor. Ambrosius Blarer, der schwäbische Reformator: aus den Quellen übersichtlich dargestellt. Stuttgart: Belser, 1860.

Pressel, Theodor. Ambrosius Blaurer. (Leben und ausgewählte Schriften der Väter und Begründer der reformierten Kirche; 9). Elberfeld : Friderichs, 1861.

Schiess, Traugott, Bearb. Briefwechsel der Brüder Ambrosius und Thomas Blaurer: 1509-1567. Freiburg : Fehsenfeld: 1908: I.

Spitta, Friedrich. Zeitschrift für historische Theologie 38 (1920): 243 ff. Article on Blaurer’s hymnal.

| Author(s) | Christian Hege |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1953 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Hege, Christian. "Blaurer, Ambrosius (1492-1564)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1953. Web. 16 Apr 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Blaurer,_Ambrosius_(1492-1564)&oldid=143963.

APA style

Hege, Christian. (1953). Blaurer, Ambrosius (1492-1564). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 16 April 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Blaurer,_Ambrosius_(1492-1564)&oldid=143963.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, pp. 353-354. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.