Anatomia humani corporis (Anatomical Atlas)

Govert Bidloo. Godefridi Bidloo, Medicinae Doctoris & Chirurgi, Anatomia Hvmani Corporis, Centum & quinque Tabvlis Per arificiosiss. G. De Lairesse ad vivum delineatis, Demonstrata, Veterum Recentiorumque Inventis explicata plurimisque, hactenus non detectis Illvstrata. Amsterdam, Netherlands. Sumptibus viduae Joannis à Someren, Haeredum Joannis à Dyk, Henrici & Viduae Theodori Boom. 1685, 69 unnumbered leaves +107 plates.

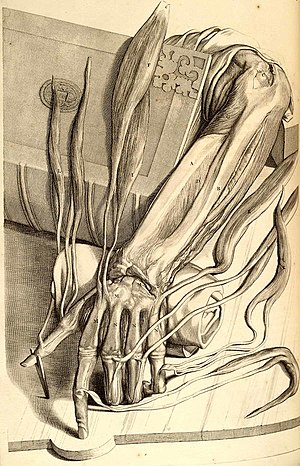

This book known under its shortened Latin name, Anatomia humani corporis [in English: Anatomy of the Human Body] is a notable anatomical atlas published in 1685 and which in 1690 the author, Bidloo, published a translated Dutch edition with the title: Ontleding des menschelyken lichaams. Govert Bidloo (1649-1713) was born in Amsterdam and was part of a noted and devout Mennonite family. As the author Bidloo wrote the text, chose the topics and form of the engravings and hired the famous artist, Gerard de Laiesse, to illustrate the atlas. The work was lavishly illustrated with an engraved titlepage, a portrait of Bidloo, plus 105 large, 53 cm. high copper plate engravings by de Laiesse and from the engraving hands of Abraham van Blooteling and Pieter van Gunst.

Today Bidloo’s atlas, Anatomia humani corporis, is recognized as presenting a paradigm shift in the style of anatomical illustration. In the many anatomical atlases published before Bidloo and some after, the illustrations of the human form or its parts attempted to present illustrations as the "perfect" human form. Thus they displayed human figures as skeletons or musclemen in live poses as on sees in classical sculpture. In this way those anatomical atlases from Reform or Catholic colleagues of Bidloo believed the perfect body demonstrated the perfection of God's creation and the soul within. However, real humans are never perfect and anatomical dissections revealed there are always differences from human perfection. In contrast for Mennonites like Bidloo the "perfect" human was one whose life, thoughts and actions most closely followed the earthly example of Christ. Perfection was not depended on body shape or idealized proportion but on how one's life was lived.

Further Bidloo's Mennonite concept of "truth" was to present anatomical drawings as "representation after life." Instead of objectifying the body he depicted the realistic images of flayed and dissected body parts as they appeared during dissection. Everyday objects such as books, jars, and even a fly, commonplace in the anatomy rooms of the day, featured alongside the limbs and dissected surfaces to bring scale and poise to the illustrations. Draped cloth was positioned to cover the genitals and faces of the cadavers, to both allow the reader to peer into the open thorax or abdomen to discover the inner workings of the flesh beneath and to bring compassion and dignity to the dead.

It is worth noting that in Amsterdam in the same year, 1685, both Bidloo published his Anatomia humani corporis and the second edition of T. J. van Braght's Martyrs' Mirror were published. Jan Luyken filled the martyr book with engravings of devout and serene Christians meeting a violent death as Christ did and in effect, though ordinary people, brought a type of human perfection through their deaths. Bidloo mirrored this and brought truth and dignity to his dead. Both Bidloo and Luyken were Lamists and lived in the small Mennonite community of Amsterdam. They no doubt knew of each other's labours.

Anatomia humani corporis had been planned as one of the most beautiful medical books ever published. Though critics praised the engravings as aesthetically pleasing, and the accompanying text was criticised as incomplete, particularly regarding muscles, the book was a poor seller. However, Anatomia humani corporis gained considerable fame due to the notorious plagiarism of the plates by the eminent English physician William Cowper (1666-1709) who in 1698 added an improved English language text, and then passed the entire work off as his own. Anatomia humani corporis furthered the development of anatomical illustrations by giving early depictions of skin and hair from observation with a microscope including the first depiction of finger prints. Over time the engravings have generated considerable thought, analysis, discussion and controversy as to how they are to be interpreted and what they meant to both Bidloo who planned and oversaw the publication and Gerard de Laiesse who turned those plans into exquisite illustrations.

Bibliography

Cuir, Raphaël. The Development of the Study of Anatomy from the Renaissance to Cartesianism : da Carpi, Vesalius, Estienne, Bidloo. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellon Press, 2009.

Rachel V Guest, Dániel Margócsy, Stephen J Wigmore. "Govert Bidloo's liver: human symmetry reflected." The Lancet 383, no. 9918 (22 February 2014): 688-689.

Rina Knoeff. "Moral Lessons of Perfection: A Comparison of Mennonite and Calvinist Motives in the Anatomical Atlases of Bidloo and Albinus." in Ole Peter Grell and Andrew Cunningham: Medicine and Religion in Enlightenment Europe. Farmham, UK: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2007: 121-143.

Additional Information

Scanned images of the entire atlas except for the Bidloo portrait are accessible at: http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/bidloo1685/

| Author(s) | Victor G. Wiebe |

|---|---|

| Date Published | August 2017 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Wiebe, Victor G.. "Anatomia humani corporis (Anatomical Atlas)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. August 2017. Web. 24 Nov 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Anatomia_humani_corporis_(Anatomical_Atlas)&oldid=154205.

APA style

Wiebe, Victor G.. (August 2017). Anatomia humani corporis (Anatomical Atlas). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 24 November 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Anatomia_humani_corporis_(Anatomical_Atlas)&oldid=154205.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.