Difference between revisions of "East Prussia"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

SamSteiner (talk | contribs) |

(Replaced article from ME with new article.) |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

Source: [http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Wikipedia Commons]'']] | Source: [http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Wikipedia Commons]'']] | ||

| − | + | === Introduction === | |

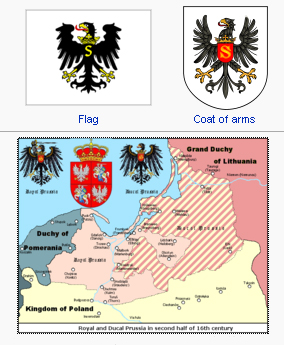

| + | East Prussia has had shifting boundaries but beginning in 1466 it stretched from Marienwerder in the west to Memel/Klaipeda in the north along the Baltic Sea coast with Königsberg as the capital. Originally inhabited by a Baltic tribe, the Old Prussians, the wider coastal area was conquered and forcibly Christianized by the Teutonic Knights during the thirteenth century. In 1525 the last Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights became a Lutheran and a duke and the territory a duchy, Ducal Prussia, since the monastic order was dissolved. In 1618 the Hohenzollern family who ruled Brandenburg inherited that duchy and in 1657 removed it from under the sovereignty of the Polish Commonwealth. The name Prussia became attached to the Brandenburg state in 1701 when the Elector Friedrich III was crowned in Königsberg as Friedrich I, King in Prussia. In 1772, the Prussian king Friedrich II seized the part of Poland, Royal Prussia, that lay between Brandenburg and Ducal Prussia as part of the First Partition of Prussia and changed the names of Royal and Ducal Prussia to West and East Prussia respectively. The main Mennonite settlements in this wider area were always in West Prussia but the smaller East Prussian congregations shared an intimate history with that larger group. | ||

| + | === Rumors and Sightings of Anabaptists and Mennonites in Ducal Prussia === | ||

| + | Many reports were made of Anabaptists and Mennonites in this territory in the sixteenth century, but no lasting congregations were founded. The pressure of persecution in the Holy Roman Empire and good trading connections between this territory and the Netherlands made this territory outside of the empire a likely place of refuge. The new Duke Albrecht granted concessions to Dutch settlers in 1527 that attracted a heterogenous group which included Anabaptists among many others. Two prominent ducal councilors with Anabaptist connections are known. Christian Entfelder, a student of Hans Denck and acquaintance of Balthasar Hubmaier, held that title starting in 1536 and Gerhard Westerburg from Cologne from 1542. It is unlikely they were still completely Anabaptist in their orientation by then. Two Dutch colonies with some Anabaptists were settled north of Preussisch Holland in 1527 and in the Rossgarten district of Königsberg in the 1520s. | ||

| − | + | In 1543 stricter proponents of Lutheran orthodoxy won the ear of the Duke and they managed to win an edict calling for the Anabaptists’ expulsion that was successfully enforced. This was the end of larger Mennonite settlements in the territory, although individual Mennonites appeared in the records of the city of Königsberg in 1579 and 1669. | |

| − | + | === East Prussian Mennonites in the Kingdom of Prussia === | |

| + | The consistently strict religious policy of the Dukes of Prussia after 1543 shifted to a more erratic course after the Hohenzollern family of Brandenburg attached the territory more firmly to their state after 1701. Friedrich I invited Mennonites into his territory in 1711, hoping to bring persecuted Swiss Mennonite settlers, but ending up with Mennonites from Poland for the most part. His son Friedrich William I repeated the invitation in 1713, now targeting Mennonites from the Vistula valley. These mostly ended up in Prussian Lithuania, where they developed a flourishing dairy industry. Their cheese, known as Tilsiter, came to dominate the Königsberg market by 1723. After a revival in 1717, some Lutherans joined the congregation, married Mennonite women, and when in 1723 they were impressed into the army and refused to serve, the king ordered their expulsion from that area, but left a small group near Rautenburg and those in Königsberg alone. Those expelled returned to Poland where a large group founded the congregation of Tragheimerweide. In 1732 when the king was trying to recruit Protestants exiled from Salzburg, he expelled all the Mennonites in the entire territory in order to make room for those better Protestant migrants. | ||

| − | In | + | In Königsberg shifts in Hohenzollern policies beginning in 1713 led to renewed immigration to Königsberg, primarily from Danzig. The two main economic activities were distilling and lace making. Especially distilling was new to the city, provided new tax revenue, and saved on imports from Danzig. Mennonites working in other areas, however, provoked the hostility of the guilds. When the expulsion order of 1732 came, local officials drew up a list of seventeen prominent Mennonite families to document their substantial economic value to the crown. The king eventually agreed to allow Mennonites to stay in the city if they paid extra but those in rural areas had to leave. When his son, Friedrich II, came to the throne in 1740, tolerance in the whole territory was restored and a community reestablished in Prussia Lithuania. |

| − | + | The Königsberg congregation purchased a house to use for services in 1752 and built a prayer house on the same location in 1769, maintaining two houses for the congregational poor and elderly since the former date. In 1772 with the First Partition of Poland, Ducal Prussia became East Prussia, and the congregations here participated in the agreements and payments made by the Mennonites along the Vistula River to maintain their military service exemption under Friedrich II. The fact that Mennonites in Poland associated coming under Prussian rule with the 1723 expulsions which in turn were linked to conversions and mixed marriages led all the congregations to agree over time to ban these processes, which were in any case made illegal by the Prussian Mennonite Edict of 1789. Mennonite social isolation from their community was thus increased as the nineteenth century began while their economic integration grew. | |

| − | In the | + | The small Königsberg congregation was quite progressive and a leader in the shift to educated, professional pastors that began in the 1820s and continued for over one hundred years in provincial Prussia. In the 1830s three young men were sponsored for theological education in German universities; one of them, Carl Harder, was from Königsberg. He was supported by Hermann Warkentin, a businessman and pastor (Lehrer) in the congregation. In 1846 he was installed as a pastor in the congregation at the age of 26. Young townspeople in Elbing, where he married Renate Thiessen that same year, called on him to preach there as well. His popularity in Elbing and the fact that under his leadership the Königsberg congregation accepted members banned in the Vistula Delta led to a schism in the Elbing-Ellerwald congregation. The small group that followed Harder built their own church in 1852 and became a branch of the Königsberg congregation. Harder served as Elder of both congregations until he moved to Neuwied in 1858. Harder founded the first Mennonite newspaper in Germany, Monatsschrift für evangelischen Mennoniten from 1846-48, and advocated for allowing mixed marriages, military service, and better integrating Mennonites into German middle-class life. His unorthodox views on baptism provoked a strong reaction among traditional Mennonites, who conspired with the government to revoke his ordination and authority as Elder, precipitating his move to Neuwied. |

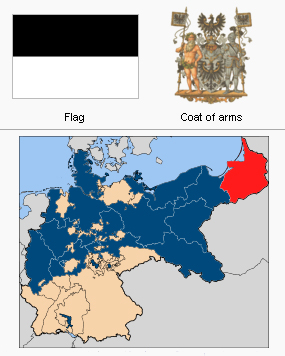

| − | + | === East Prussian Mennonites in the German Empire === | |

| + | The founding of the German Reich in 1871 was proceeded in 1868 by the requirement that all Mennonites serve in the military either as regular soldiers or as non-combatants. In 1874 a new Mennonite Law removed virtually all the restrictions on Mennonites’ civil rights that had been imposed by the Edict of 1789. These changes did not cause problems in the congregations of East Prussia, one measure of which would be the lack of outmigration at the time over the issue, quite unlike what happened in the congregations of West Prussia. Carl Harder was able to return to Elbing in 1868 und took up leadership of both the Elbing and Königsberg congregations again until his death in 1898. | ||

| − | + | In 1869 the congregation in Prussia Lithuania included 774 people while in 1882 Königsberg only had fifty members. The Königsberg congregation was a founding member of the more liberal conference Alliance of Mennonite Congregations in the German Empire (Vereinigung) and in 1899 transferred control of its capital fund of 125,000 Marks to the Alliance with some proceeds still flowing back to the congregation. In World War I only a handful of East Prussian Mennonites made use of the provision that they could serve as non-combatants. The hyperinflation of the 1920s caused the congregation in Prussian Lithuania to revert to lay preachers. | |

| − | + | === Nazi Rule, War, and the Dissolution of the Congregations === | |

| + | After World War I the western border of East Prussia was extended to the Nogat River. On the other side was the Free State of Danzig, created by the Treaty of Versailles. Thus many more Mennonite congregations were added to East Prussia; Elbing, Elbing-Ellerwald, Thiensdorf-Markushof, Tragheimerweide, and the Heubuden branch in Marienburg. Not many details of the East Prussian Mennonites’ attitudes toward the Nazi regime are documented but given the early commitment to military service and German nationalism here, most were likely favorable. Bruno Götzke, the last Elder in Prussian Lithuania, was also the mayor of Neukirch and head of the local school board under the Nazis. | ||

| − | + | This congregation was evacuated to near Königsberg in October 1944, with most of the men being drafted, but when the Soviets surrounded the city in January in January 1945 those women, children, and elderly who survived were sent home, but soon deported to post-war Germany. Königsberg was under siege until April. Some Mennonites had managed to flee, others like the last Elder Josef Gingerich stayed in the city. He finally left for Bavaria in 1947 as one of the last Mennonites still in East Prussia. After a three-year imprisonment by the Soviets, Götzke ended up in the Soviet-occupied zone of Germany where he visited scattered Mennonite refugees and held worship services in various locales, helping to establish the church in what became the German Democratic Republic. He fled for West Germany in 1953. | |

| + | == Bibliography (Selected) == | ||

| − | + | Crous, Ernst. ''Karl und Ernst Harder: ein Nachruf''. Elbing: Reinhold Kühn, 1927. | |

| − | + | Gerlach, Horst. "The Final Years of Mennonites in East and West Prussia, 1943-1945," in ''Mennonite Quarterly Review'', 66, 2 and 3, (April and July 1992): 221-246, 391-423. | |

| − | + | Jantzen, Mark. ''Mennonite German Soldiers. Nation, Religion, and Family in the Prussian East, 1772-1880''. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2010. | |

| − | + | Jantzen, Mark. "The Trouble with Marrying Prussian Lutheran Boys: The End of Exogamous Marriages in the Mennonite Community in the Polish Vistula Delta, 1713-1808" in: Mirjam van Veen et al (eds.), ''Sisters: Myth and Reality of Anabaptist, Mennonite, and Doopsgezind Women ca. 1525-1900''. Amsterdam: Brill, 2014: 285-301. | |

| − | + | Mannhardt, Wilhelm. ''Die Wehrfreiheit der altpreussischen Mennoniten''. Eine geschichtliche Erörterung. Marienburg: Komm Helmpels, 1863. | |

| − | + | Penner, Horst. "Christian Entfelder. Ein mährischer Täuferprediger und herzoglicher Rat am Hofe Albrechts von Preußen," in: ''Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter'' 23 (1966): 19-23. | |

| − | + | Penner, Horst. ''Die ost- und westpreußischen Mennoniten in ihrem religiösen und sozialen Leben in ihren kulturellen und wirtschaftlichen Leistungen''. Tl. I, 1526 bis 1772; Tl. II, Von 1772 bis zur Gegenwart. Weierhof: Mennonitischer Geschichtsverein, 1978; Kirchheimbolanden: Horst Penner, 1987. | |

| − | + | Penner, Horst. "Ostpreußen" in ''Mennonitisches Lexikon'', 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III, 322-25. | |

| − | + | Randt, Erich. ''Die Mennoniten in Ostpreußen und Litauen bis zum Jahre 1772''. Königsberg: Otto Rümmel, 1912. | |

| − | + | Wittenberg, Erwin und Manuel Janz. "Geschichte der mennonitischen Siedler in Preußischen Litauen." ''Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter'' 74 (2017): 73-97. | |

| − | + | {{GAMEO_footer|hp=|date=January 2026|a1_last=Jantzen|a1_first=Mark|a2_last= |a2_first= }} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{GAMEO_footer|hp= | ||

[[Category:Places]] | [[Category:Places]] | ||

Revision as of 20:52, 17 January 2026

Source: Wikipedia Commons

Introduction

East Prussia has had shifting boundaries but beginning in 1466 it stretched from Marienwerder in the west to Memel/Klaipeda in the north along the Baltic Sea coast with Königsberg as the capital. Originally inhabited by a Baltic tribe, the Old Prussians, the wider coastal area was conquered and forcibly Christianized by the Teutonic Knights during the thirteenth century. In 1525 the last Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights became a Lutheran and a duke and the territory a duchy, Ducal Prussia, since the monastic order was dissolved. In 1618 the Hohenzollern family who ruled Brandenburg inherited that duchy and in 1657 removed it from under the sovereignty of the Polish Commonwealth. The name Prussia became attached to the Brandenburg state in 1701 when the Elector Friedrich III was crowned in Königsberg as Friedrich I, King in Prussia. In 1772, the Prussian king Friedrich II seized the part of Poland, Royal Prussia, that lay between Brandenburg and Ducal Prussia as part of the First Partition of Prussia and changed the names of Royal and Ducal Prussia to West and East Prussia respectively. The main Mennonite settlements in this wider area were always in West Prussia but the smaller East Prussian congregations shared an intimate history with that larger group.

Rumors and Sightings of Anabaptists and Mennonites in Ducal Prussia

Many reports were made of Anabaptists and Mennonites in this territory in the sixteenth century, but no lasting congregations were founded. The pressure of persecution in the Holy Roman Empire and good trading connections between this territory and the Netherlands made this territory outside of the empire a likely place of refuge. The new Duke Albrecht granted concessions to Dutch settlers in 1527 that attracted a heterogenous group which included Anabaptists among many others. Two prominent ducal councilors with Anabaptist connections are known. Christian Entfelder, a student of Hans Denck and acquaintance of Balthasar Hubmaier, held that title starting in 1536 and Gerhard Westerburg from Cologne from 1542. It is unlikely they were still completely Anabaptist in their orientation by then. Two Dutch colonies with some Anabaptists were settled north of Preussisch Holland in 1527 and in the Rossgarten district of Königsberg in the 1520s.

In 1543 stricter proponents of Lutheran orthodoxy won the ear of the Duke and they managed to win an edict calling for the Anabaptists’ expulsion that was successfully enforced. This was the end of larger Mennonite settlements in the territory, although individual Mennonites appeared in the records of the city of Königsberg in 1579 and 1669.

East Prussian Mennonites in the Kingdom of Prussia

The consistently strict religious policy of the Dukes of Prussia after 1543 shifted to a more erratic course after the Hohenzollern family of Brandenburg attached the territory more firmly to their state after 1701. Friedrich I invited Mennonites into his territory in 1711, hoping to bring persecuted Swiss Mennonite settlers, but ending up with Mennonites from Poland for the most part. His son Friedrich William I repeated the invitation in 1713, now targeting Mennonites from the Vistula valley. These mostly ended up in Prussian Lithuania, where they developed a flourishing dairy industry. Their cheese, known as Tilsiter, came to dominate the Königsberg market by 1723. After a revival in 1717, some Lutherans joined the congregation, married Mennonite women, and when in 1723 they were impressed into the army and refused to serve, the king ordered their expulsion from that area, but left a small group near Rautenburg and those in Königsberg alone. Those expelled returned to Poland where a large group founded the congregation of Tragheimerweide. In 1732 when the king was trying to recruit Protestants exiled from Salzburg, he expelled all the Mennonites in the entire territory in order to make room for those better Protestant migrants.

In Königsberg shifts in Hohenzollern policies beginning in 1713 led to renewed immigration to Königsberg, primarily from Danzig. The two main economic activities were distilling and lace making. Especially distilling was new to the city, provided new tax revenue, and saved on imports from Danzig. Mennonites working in other areas, however, provoked the hostility of the guilds. When the expulsion order of 1732 came, local officials drew up a list of seventeen prominent Mennonite families to document their substantial economic value to the crown. The king eventually agreed to allow Mennonites to stay in the city if they paid extra but those in rural areas had to leave. When his son, Friedrich II, came to the throne in 1740, tolerance in the whole territory was restored and a community reestablished in Prussia Lithuania.

The Königsberg congregation purchased a house to use for services in 1752 and built a prayer house on the same location in 1769, maintaining two houses for the congregational poor and elderly since the former date. In 1772 with the First Partition of Poland, Ducal Prussia became East Prussia, and the congregations here participated in the agreements and payments made by the Mennonites along the Vistula River to maintain their military service exemption under Friedrich II. The fact that Mennonites in Poland associated coming under Prussian rule with the 1723 expulsions which in turn were linked to conversions and mixed marriages led all the congregations to agree over time to ban these processes, which were in any case made illegal by the Prussian Mennonite Edict of 1789. Mennonite social isolation from their community was thus increased as the nineteenth century began while their economic integration grew.

The small Königsberg congregation was quite progressive and a leader in the shift to educated, professional pastors that began in the 1820s and continued for over one hundred years in provincial Prussia. In the 1830s three young men were sponsored for theological education in German universities; one of them, Carl Harder, was from Königsberg. He was supported by Hermann Warkentin, a businessman and pastor (Lehrer) in the congregation. In 1846 he was installed as a pastor in the congregation at the age of 26. Young townspeople in Elbing, where he married Renate Thiessen that same year, called on him to preach there as well. His popularity in Elbing and the fact that under his leadership the Königsberg congregation accepted members banned in the Vistula Delta led to a schism in the Elbing-Ellerwald congregation. The small group that followed Harder built their own church in 1852 and became a branch of the Königsberg congregation. Harder served as Elder of both congregations until he moved to Neuwied in 1858. Harder founded the first Mennonite newspaper in Germany, Monatsschrift für evangelischen Mennoniten from 1846-48, and advocated for allowing mixed marriages, military service, and better integrating Mennonites into German middle-class life. His unorthodox views on baptism provoked a strong reaction among traditional Mennonites, who conspired with the government to revoke his ordination and authority as Elder, precipitating his move to Neuwied.

East Prussian Mennonites in the German Empire

The founding of the German Reich in 1871 was proceeded in 1868 by the requirement that all Mennonites serve in the military either as regular soldiers or as non-combatants. In 1874 a new Mennonite Law removed virtually all the restrictions on Mennonites’ civil rights that had been imposed by the Edict of 1789. These changes did not cause problems in the congregations of East Prussia, one measure of which would be the lack of outmigration at the time over the issue, quite unlike what happened in the congregations of West Prussia. Carl Harder was able to return to Elbing in 1868 und took up leadership of both the Elbing and Königsberg congregations again until his death in 1898.

In 1869 the congregation in Prussia Lithuania included 774 people while in 1882 Königsberg only had fifty members. The Königsberg congregation was a founding member of the more liberal conference Alliance of Mennonite Congregations in the German Empire (Vereinigung) and in 1899 transferred control of its capital fund of 125,000 Marks to the Alliance with some proceeds still flowing back to the congregation. In World War I only a handful of East Prussian Mennonites made use of the provision that they could serve as non-combatants. The hyperinflation of the 1920s caused the congregation in Prussian Lithuania to revert to lay preachers.

Nazi Rule, War, and the Dissolution of the Congregations

After World War I the western border of East Prussia was extended to the Nogat River. On the other side was the Free State of Danzig, created by the Treaty of Versailles. Thus many more Mennonite congregations were added to East Prussia; Elbing, Elbing-Ellerwald, Thiensdorf-Markushof, Tragheimerweide, and the Heubuden branch in Marienburg. Not many details of the East Prussian Mennonites’ attitudes toward the Nazi regime are documented but given the early commitment to military service and German nationalism here, most were likely favorable. Bruno Götzke, the last Elder in Prussian Lithuania, was also the mayor of Neukirch and head of the local school board under the Nazis.

This congregation was evacuated to near Königsberg in October 1944, with most of the men being drafted, but when the Soviets surrounded the city in January in January 1945 those women, children, and elderly who survived were sent home, but soon deported to post-war Germany. Königsberg was under siege until April. Some Mennonites had managed to flee, others like the last Elder Josef Gingerich stayed in the city. He finally left for Bavaria in 1947 as one of the last Mennonites still in East Prussia. After a three-year imprisonment by the Soviets, Götzke ended up in the Soviet-occupied zone of Germany where he visited scattered Mennonite refugees and held worship services in various locales, helping to establish the church in what became the German Democratic Republic. He fled for West Germany in 1953.

Bibliography (Selected)

Crous, Ernst. Karl und Ernst Harder: ein Nachruf. Elbing: Reinhold Kühn, 1927.

Gerlach, Horst. "The Final Years of Mennonites in East and West Prussia, 1943-1945," in Mennonite Quarterly Review, 66, 2 and 3, (April and July 1992): 221-246, 391-423.

Jantzen, Mark. Mennonite German Soldiers. Nation, Religion, and Family in the Prussian East, 1772-1880. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2010.

Jantzen, Mark. "The Trouble with Marrying Prussian Lutheran Boys: The End of Exogamous Marriages in the Mennonite Community in the Polish Vistula Delta, 1713-1808" in: Mirjam van Veen et al (eds.), Sisters: Myth and Reality of Anabaptist, Mennonite, and Doopsgezind Women ca. 1525-1900. Amsterdam: Brill, 2014: 285-301.

Mannhardt, Wilhelm. Die Wehrfreiheit der altpreussischen Mennoniten. Eine geschichtliche Erörterung. Marienburg: Komm Helmpels, 1863.

Penner, Horst. "Christian Entfelder. Ein mährischer Täuferprediger und herzoglicher Rat am Hofe Albrechts von Preußen," in: Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter 23 (1966): 19-23.

Penner, Horst. Die ost- und westpreußischen Mennoniten in ihrem religiösen und sozialen Leben in ihren kulturellen und wirtschaftlichen Leistungen. Tl. I, 1526 bis 1772; Tl. II, Von 1772 bis zur Gegenwart. Weierhof: Mennonitischer Geschichtsverein, 1978; Kirchheimbolanden: Horst Penner, 1987.

Penner, Horst. "Ostpreußen" in Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III, 322-25.

Randt, Erich. Die Mennoniten in Ostpreußen und Litauen bis zum Jahre 1772. Königsberg: Otto Rümmel, 1912.

Wittenberg, Erwin und Manuel Janz. "Geschichte der mennonitischen Siedler in Preußischen Litauen." Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter 74 (2017): 73-97.

| Author(s) | Mark Jantzen |

|---|---|

| Date Published | January 2026 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Jantzen, Mark. "East Prussia." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. January 2026. Web. 5 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=East_Prussia&oldid=181471.

APA style

Jantzen, Mark. (January 2026). East Prussia. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 5 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=East_Prussia&oldid=181471.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.