Difference between revisions of "Jung-Stilling, Johann Heinrich (1740-1817)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (Sorted bibliography.) |

m (Text replace - "<em>Mennonitisches Lexikon</em>" to "''Mennonitisches Lexikon''") |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

Günther, H. R. G. <em>Jung-Stilling.</em> 1928. | Günther, H. R. G. <em>Jung-Stilling.</em> 1928. | ||

| − | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. | + | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. ''Mennonitisches Lexikon'', 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe; Schneider, 1913-1967: v. 3, 446 f. |

Herzog, J. J. and Albert Hauck, <em>Realencyclopedie für Protestantische Theologie and Kirche</em>, 24 vols. 3rd ed. Leipzig: J. H. Hinrichs, 1896-1913: v. 19, 46 ff. | Herzog, J. J. and Albert Hauck, <em>Realencyclopedie für Protestantische Theologie and Kirche</em>, 24 vols. 3rd ed. Leipzig: J. H. Hinrichs, 1896-1913: v. 19, 46 ff. | ||

Revision as of 07:31, 16 January 2017

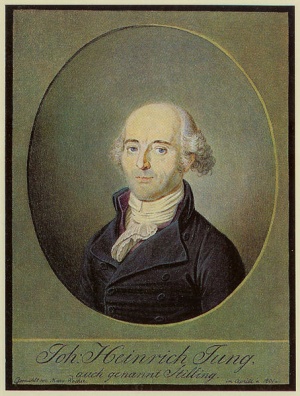

Johann Heinrich Jung-Stilling, (1740-1817): Pietist, physician and economist; born 12 September 1740, in Grund near Hilchenbach, Westphalia, Germany, the son of a tailor and schoolmaster. At the age of 15 he became a schoolteacher at Litzel, where he came in contact with religious separatists, and worked as teacher and tailor, learned the treatment of the eye from a Catholic priest, and studied this science at Strasbourg (1770-72), where he made the acquaintance of Goethe and Herder, practiced medicine in Elberfeld, acquired fame for his operation on cataracts (1773-78), lectured on technical subjects in the Kameralschule at Kaiserslautern (1778-84), and became professor at Marburg, then at Heidelberg (1784-1803), was made councilor of Charles Frederick, Grand Duke of Baden, in Heidelberg (18037), and was finally pensioned by the duke and spent his last years at Karlsruhe (1807-17). Throughout his life his first interest lay in serving the kingdom of God.

Through his numerous writings, his extensive correspondence, and frequent journeys, Jung-Stilling left traces of his influence in many places, including the Mennonite communities. Among his works, his Lebensgeschichte, particularly Jugend and Wanderschaft, the novel Heimweh, the periodical Der graue Mann; Biblische Erzählungen, and the novel Theobald oder die Schwärmer, were read widely in Mennonite families, especially in the Palatinate. In his autobiography, Heinrich Stillings Wanderschaft (Berlin and Leipzig, 1778, 47 f.), he relates that he worked for a tailor Isaak (I. Becker) at Rade vor dem Walde (Waldstätt) and was beneficially stimulated in religious thought by him. This man was apparently a Swiss Mennonite emigrant (Menn. BI., 139; Heimweh I, 77). Jung-Stilling speaks in some detail about the Mennonites in his Taschenbuch für Freunde des Christentums, publishing a picture of Menno Simons, defending them against unjust accusations, and praising their Christian foundation and character (Menn. BI., 1890, p. 62; Gbl., 1899, p. 83).

He also makes an interesting remark about the Palatinate Mennonites in Heimweh: "The pastor in Kaiserslautern was called to account, because he had permitted a Mennonite woman to be buried in the churchyard, and had attended the funeral." Obviously these words refer to the case of religious intolerance described in detail in Gem.-Kal. 1909, 63 ff. In this allegorical novel, Heimweh, he pays a tribute to the Swiss Mennonite way of life by having his hero Eugenius meet his bride-to-be in a Swiss Mennonite home, where he also receives his most impressive lessons on faith.

In May 1785 Jung-Stilling and his wife visited the Mennonite David Möllinger, the "father of clover culture in the Palatinate," at Monsheim, whose album contains the following entry in verse: "Certainly the man does not live in vain, who always knows his intentions, himself, and his duty. In memory of Salome Jung, nee St. George" (d. 25 May 1790).

"Friend Möllinger! Here I cannot make verses; for my heart is too full of thanks to the heavenly Father, too full of bliss to think of rhymes; Möllinger and Stilling, two brothers whom the Lord has raised from the dust, should be filled with nothing but thanks and praise to their Creator and Preserver." Jung-Stilling signs himself "Möllinger's brother, Dr. Johann Heinrich Jung, grand ducal councilor and professor at Heidelberg, Monsheim, May 2, 1785."

With the Palatine Mennonites, Johann Risser of Friedelsheim, B. Eymann of Kindenheim, and Jakob Krehbiel of Weierhof, Jung-Stilling carried on an extensive correspondence. The occasion for the correspondence was probably the conversion of a young Jew, Heinrich Wilhelm David Hamann, who was won for Christianity by his contacts with the Mennonites. Jung-Stilling became interested in him and arranged his journey to England, where he was trained as a missionary to the Jews (in Basel, 1844-73).

Jung-Stilling's hymn, "Vater, deines Geistes Wehen," was adopted in the hymnal of the South German Mennonites of 1910 (No. 170).

Jung-Stilling also had some influence on the Mennonites of Russia. Some of the Mennonites in Russia were so impressed by his description in Heimweh (to some extent also by other similar literature) of an imaginary oriental theocracy near the Aral Sea that they founded a colony there, expecting to find in it the refuge from the anti-Christ pictured allegorically by Jung-Stilling. Franz Bartsch (Unser Auszug, 8) says: "The reading of Jung-Stilling's writings, e.g., his Heimweh, had given the first impetus [to the idea]."

Bibliography

Bartsch, Fr. Unser Auszug nach Mittelasien. Halbstadt, 1907: 8.

Correll, E. H. Das schweizerische Täufermennonitentum. Tubingen, 1925: 112 ff.

Günther, H. R. G. Jung-Stilling. 1928.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe; Schneider, 1913-1967: v. 3, 446 f.

Herzog, J. J. and Albert Hauck, Realencyclopedie für Protestantische Theologie and Kirche, 24 vols. 3rd ed. Leipzig: J. H. Hinrichs, 1896-1913: v. 19, 46 ff.

Die Religion in Geschichte and Gegenwart, 2. ed., 5 vols. Tübingen: Mohr, 1927-1932: v. 3, Col. 468.

Stecher, G. Jung-Stilling als Schriftsteller. 1913.

Vömel, A. Briefe Jung-Stilling an seine Freunde Wiegand and Grieber. 1905.

Neff, Christian. "Jung-Stilling über Menno Simons." Contains 3 letters from Jung-Stilling Johannes Risser) in Mennonitischer Gemeinde-Kalender (1937): 49.53.

Neff, Christian. "Jung-Stilling und die Mennoniten." Menn. Jugendwarte 18 (1938): 36-45, 56-66, 80-88. Contains letters from Jung-Stilling to David Möllinger, J. J. Becker, and Jacob Krehbiel.

| Author(s) | Christian Neff |

|---|---|

| Elizabeth Horsch Bender | |

| Date Published | 1955 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Neff, Christian and Elizabeth Horsch Bender. "Jung-Stilling, Johann Heinrich (1740-1817)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1955. Web. 2 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Jung-Stilling,_Johann_Heinrich_(1740-1817)&oldid=146522.

APA style

Neff, Christian and Elizabeth Horsch Bender. (1955). Jung-Stilling, Johann Heinrich (1740-1817). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 2 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Jung-Stilling,_Johann_Heinrich_(1740-1817)&oldid=146522.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 3, pp. 127-128. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.