Difference between revisions of "Forsteidienst"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (→1989 Update) |

m (→1956 Article) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

__TOC__ | __TOC__ | ||

== 1956 Article == | == 1956 Article == | ||

| − | Forestry Service <em>(Forsteidienst), </em>the alternative service rendered in lieu of military duty by the Russian Mennonites. In 1874 universal [[Conscription|conscription]] was introduced in [[Russia|Russia]]. The proposal to pass such a measure, which was announced in 1870, was a cause of great concern to the Mennonites, who at all costs wanted to remain true to their principle of [[Nonresistance|nonresistance]], a privilege promised them when they immigrated. They sent deputation after deputation to St. Petersburg to secure release from military duty. When this effort seemed to be futile, the great emigration of Russian Mennonites ensued. | + | Forestry Service <em>(Forsteidienst),</em> was the alternative service rendered in lieu of military duty by the Russian Mennonites. In 1874 universal [[Conscription|conscription]] was introduced in [[Russia|Russia]]. The proposal to pass such a measure, which was announced in 1870, was a cause of great concern to the Mennonites, who at all costs wanted to remain true to their principle of [[Nonresistance|nonresistance]], a privilege promised them when they immigrated. They sent deputation after deputation to St. Petersburg to secure release from military duty. When this effort seemed to be futile, the great emigration of Russian Mennonites ensued. |

But the authorities, who had learned to appreciate the Mennonites as competent farmers and as an important cultural asset, did not want to lose the contributions this group was making to the cultivation of the land. The government therefore proposed to the Mennonites a system of release from military service by service (1) in the shops of the Navy Department; (2) in fire companies, or (3) in mobile companies in the Forestry Department. Service in the medical corps, which had been considered by the government committees, was rejected by the Mennonites on the grounds that in time of war the medical corps was directly involved in the war effort. The third of the proposed systems was accepted. The Mennonites now planned to keep their young men together in large groups in order to provide pastoral care for them and to keep them from foreign influence. They accordingly sent a deputation to St. Petersburg with a petition to allow them to render their alternative service in fixed forestry companies under civilian government authority, and as much as possible in the neighborhood of a Mennonite settlement. | But the authorities, who had learned to appreciate the Mennonites as competent farmers and as an important cultural asset, did not want to lose the contributions this group was making to the cultivation of the land. The government therefore proposed to the Mennonites a system of release from military service by service (1) in the shops of the Navy Department; (2) in fire companies, or (3) in mobile companies in the Forestry Department. Service in the medical corps, which had been considered by the government committees, was rejected by the Mennonites on the grounds that in time of war the medical corps was directly involved in the war effort. The third of the proposed systems was accepted. The Mennonites now planned to keep their young men together in large groups in order to provide pastoral care for them and to keep them from foreign influence. They accordingly sent a deputation to St. Petersburg with a petition to allow them to render their alternative service in fixed forestry companies under civilian government authority, and as much as possible in the neighborhood of a Mennonite settlement. | ||

Revision as of 19:32, 5 February 2015

1956 Article

Forestry Service (Forsteidienst), was the alternative service rendered in lieu of military duty by the Russian Mennonites. In 1874 universal conscription was introduced in Russia. The proposal to pass such a measure, which was announced in 1870, was a cause of great concern to the Mennonites, who at all costs wanted to remain true to their principle of nonresistance, a privilege promised them when they immigrated. They sent deputation after deputation to St. Petersburg to secure release from military duty. When this effort seemed to be futile, the great emigration of Russian Mennonites ensued.

But the authorities, who had learned to appreciate the Mennonites as competent farmers and as an important cultural asset, did not want to lose the contributions this group was making to the cultivation of the land. The government therefore proposed to the Mennonites a system of release from military service by service (1) in the shops of the Navy Department; (2) in fire companies, or (3) in mobile companies in the Forestry Department. Service in the medical corps, which had been considered by the government committees, was rejected by the Mennonites on the grounds that in time of war the medical corps was directly involved in the war effort. The third of the proposed systems was accepted. The Mennonites now planned to keep their young men together in large groups in order to provide pastoral care for them and to keep them from foreign influence. They accordingly sent a deputation to St. Petersburg with a petition to allow them to render their alternative service in fixed forestry companies under civilian government authority, and as much as possible in the neighborhood of a Mennonite settlement.

In June 1880, after lengthy negotiations, Councillor Bark informed the Mennonite elders of the decision: Mennonite young men under military obligations would be employed in the forests of South Russia; but the Mennonites were to assume the expense of building the barracks and also provide for the food and clothing of the companies. In return the government would pay each young man in service 20 kopeks per working day. On 19 September 1880 the plan became obligatory for all the Mennonites of Russia. Six barracks were to be built within three years. In the spring of 1881 the first young men were drafted into forestry service. Soon two additional barracks were built and in the course of time the "Phylloxera" company was added.

All matters of the forestry service were regulated on the Mennonite side by the "Delegate Meeting for Forestry Service Affairs." Its executive officer was called the "Forestry President" or simply "President." It was his duty to settle all questions with the government, to provide for the welfare of the men in service, and to be in charge of the economic affairs of the companies. Each company had an "Oekonom-Prediger," who was usually known as "Papa" by the men in service; he had charge of the material care of the companies and the pastoral care. The assignment and supervision of the jobs was taken care of by government officials. Each forestry unit had a forester with the rank of captain, and an assistant, usually with the rank of lieutenant. From the ranks of the men in service an "elder" was chosen with the rank of a non-commissioned officer, and several corporals. Usually these persons were appointed by the forester after suggestion by the departing elder; but sometimes they were also elected by majority vote, and then proposed to the forester for appointment. Neither the elder nor the corporals received from the men in service any military salute or other military honor. The elder had the duty of assigning and supervising the jobs of the company and preserving discipline in the barracks. Every evening he had to give a report to the forester or his assistant on the work done; the corporals supervised the smaller subdivisions and jobs of the company.

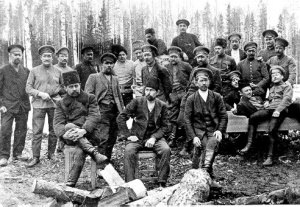

The object of these forestry units was to plant forests on a large scale in the steppes of South Russia, to lay out nurseries, and to raise model orchards. Every year many improved trees both for fruit and for forests were given free of charge to the Russians living in the neighborhood to create in them a desire to plant orchards and woods.

The work of the Phylloxera units, which served principally in Crimea and were active only six months in the year (whereas the other companies received only a few weeks or at most three months of vacation in winter), consisted in finding and exterminating the aphid Phylloxera in the vineyards. The men in service were not called soldiers, but in the records were designated as "obligatory workers." Detailed annual reports of the forestry service were published in German and Russian, e.g., Jahresbericht des Bevollmächtigten der Mennonitengemeinden in Russland in Sachen der Unterhaltung der Forstkommandos im Jahre 1907. -- Abraham Braun

In 1917 a change was made in the management of forestry service in so far as they concerned the Mennonites. During World War I about 14,000 Mennonites had been mobilized, about half of whom were engaged in forestry service. These 7,000 forestry workers were scattered into all parts of Russia, in larger and small groups.

During the Revolution and the movement for freedom that initially accompanied it there was also enthusiastic and extensive activity in organization in these groups. This circumstance, as well as the fact that providing for the men in service had been made difficult by the rise in the cost of living and the scattered state of the units, led to the appointment by the meeting of the delegates of the Mennonite congregations, together with the delegates of the men in service, held at Halbstadt in August 1917 of a committee for the management of forestry matters, with the shortened name "Iksume" (Executive committee of the delegate meeting of the Mennonite congregations). The first chairman of the committee was the former president. The committee provided for the preservation of the economic and legal interests of the men in service, which had become very difficult in the impoverished state of affairs in the throes of the revolution; it had become necessary to draft and harness all the forces on which the committee had its historical basis. A further task of the committee was to keep an account with regard to the care of clothing and traveling of the various forestry committees and the individuals still in service after demobilization in 1918.

In consequence of the unstable political conditions in 1918-1919 any orderly operation of the forestry service became impossible. When business operation of the units, which was in some places quite profitable, was threatened, the Mennonites proceeded to liquidate the forestry units, without, however, wanting to give up the forestry service as such as a matter of principle. For the purpose of this liquidation committee members were now and then delegated, who succeeded, often at the danger of their life, in disposing advantageously of the stock of cattle, products, equipment, and materials; only in a few minor cases had the forestry services already been plundered by the surrounding population. Thus the forestry service was abandoned and not resumed. -- Th. Block

1989 Update

From 1880 to 1917 Russian Mennonites were permitted by legislation to fulfill their military obligations by working in forestry camps under civilian administration. A total of nine main camps, and a mobile phyloxera unit in the Crimean peninsula were opened during these years.

The first two camps at Veliko Anadol and Azov were started up near the Bergthal Colony in the Ekaterinoslav government to admit the recruits of 1880. The next two camps, Ratzyn and Vladimirov began operating in the Kherson government during the following year, while the last two of the initial six, Neu and Alt Berdian, were established in the Taurian government, not far from the Molotschna Colony, in 1883. The Crimean phyloxera unit came into existence not long afterwards.

After the Russo-Japanese war (1904-05), two more camps were set up at Ananiev (also known as Sherebkovo) and Snamenka. (known as Chernoleskoi or Schwarzwald). Both were located north of Odessa. Early in 1914, the first year of the war, still another camp was pressed into service at Issyl Kul, a point on the Siberian railway, halfway between the cities of Omsk and Petropavlovsk.

During these four decades the total number of recruits rose from the initial group of 123 in the first two camps, to somewhat over 1,200 in the 10 sites managed by the Mennonites by 1914. David Klaassen and Henry B. Janz successively chaired IKSUMO, the organization which directed the forestry service program during the final years.

About 7,000 Mennonites served in forestry work during World War I. The majority of them were stationed outside the regular camps at other sites designated for alternative service. By the summer of 1918, all the servicemen had been demobilized and the camps were then shut permanently. Lenin's decrees of October 1918 and January 1919 continued to make military exemptions possible, but all service units were now run by the state. Some assignments to forest work, particularly in Siberia, continued right up to the time when alternative forms of service ended altogether around 1936. -- Lawrence Klippenstein

Bibliography

Friesen, Peter M. The Mennonite Brotherhood in Russia (1789-1910), trans. J. B. Toews, et al. Fresno, CA : Board of Christian Literature, 1980.

Friesen, Peter M. Die Alt-Evangelische Mennonitische Brüderschaft in Russland (1789-1910) im Rahmen der mennonitischen Gesamtgeschichte. Halbstadt: Verlagsgesellschaft "Raduga", 1911.

Görz, Abr. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Forstdienstes der Mennoniten in Russland. Gross-Tokmak, 1907.

Guenther, Waldemar, D. P. Heidebrecht, and Gerhard I. Peters. Onsi Tjedils: Ersatzdienst der Mennoniten in Russland unter den Romanows. Abbotsford, B.C.: the Authors, 1966.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. II, 663-665.

Klippenstein, Lawrence. "Mennonite Pacifism and State Service in Russia: a Case Study in Church-State Relations, 1789-1936." Ph.D. diss., U. of Minnesota, 1984.

Peters, F. C. "Non-Combatant Service Then and Now." Mennonite Life 10 (1955): 31-35.

Quiring, Walter and Helen Bartel, eds. In the Fullness of Time: 150 Years of Mennonite Sojourn in Russia, trans. by Aaron Klassen. Kitchener, ON: Aaron Klassen 1974.

Rempel, Hans and George Epp. Waffen der Wehrlosen: Ersatzdienst der Mennoniten in UdSSR. Winnipeg: CMBC Publications, 1980.

Sudermann, Jacob. "Origin of Mennonite State Service in Russia 1870-80." Mennonite Quarterly Review 17 (1943): 23-46.

Toews, John B. Czars, Soviets and Mennonites. Newton, KS: Faith and Life Press, 1982.

| Author(s) | Abraham Braun |

|---|---|

| Th. Block | |

| Lawrence Klippenstein | |

| Date Published | 1989 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Braun, Abraham, Th. Block and Lawrence Klippenstein. "Forsteidienst." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1989. Web. 2 Feb 2026. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Forsteidienst&oldid=130673.

APA style

Braun, Abraham, Th. Block and Lawrence Klippenstein. (1989). Forsteidienst. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 2 February 2026, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Forsteidienst&oldid=130673.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 353-354; vol. 5, p. 308. All rights reserved.

©1996-2026 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.