Difference between revisions of "Memrik Mennonite Settlement (Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (Text replace - "<em>Mennonitisches Lexikon</em>" to "''Mennonitisches Lexikon''") |

m (Added hyperlink.) |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

The necessary qualifications of a settler were that "the head of the [[Landless (Landlose)|landless]] family conduct a quiet and moral life, be industrious and in possession of a wagon, plow, harrow, two horses, two cows, and the necessary means to establish a home." The land was mostly unbroken prairie. Although the quality of the land was excellent the settlers underwent the usual difficulties of pioneering. All settlers were expected to repay the loan and interest within 15 years to the [[Molotschna Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Molotschna settlement]], which sponsored the settlement. Originally Memrik was under the administration of the Molotschna settlement. Because the distance was over a hundred miles, Memrik tried to establish its own district or volost administration but failed. In 1888, contrary to the wishes of the settlers, it was incorporated in the neighboring Russian Golitzynov. The group was represented in this office by a settlement leader. The following served in this capacity: Heinrich Martins, Daniel Abrahams, Peter Dirks, Johann Köhn, and Julius Dörksen. In 1921 the settlement had its own volost office and administration for a short time. The settlement also had its own fire insurance agency, organized in 1901; Hermann Janzen, Jr., was its administrator for many years. | The necessary qualifications of a settler were that "the head of the [[Landless (Landlose)|landless]] family conduct a quiet and moral life, be industrious and in possession of a wagon, plow, harrow, two horses, two cows, and the necessary means to establish a home." The land was mostly unbroken prairie. Although the quality of the land was excellent the settlers underwent the usual difficulties of pioneering. All settlers were expected to repay the loan and interest within 15 years to the [[Molotschna Mennonite Settlement (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Molotschna settlement]], which sponsored the settlement. Originally Memrik was under the administration of the Molotschna settlement. Because the distance was over a hundred miles, Memrik tried to establish its own district or volost administration but failed. In 1888, contrary to the wishes of the settlers, it was incorporated in the neighboring Russian Golitzynov. The group was represented in this office by a settlement leader. The following served in this capacity: Heinrich Martins, Daniel Abrahams, Peter Dirks, Johann Köhn, and Julius Dörksen. In 1921 the settlement had its own volost office and administration for a short time. The settlement also had its own fire insurance agency, organized in 1901; Hermann Janzen, Jr., was its administrator for many years. | ||

| − | During the 1890s some Molotschna Mennonites purchased and settled on a part of a large estate some 12 miles (20 km) from the Memrik settlement, which they named Ossokino. In the center of the settlement they built their school, which also served on Sunday for worship. The settlers belonged to the Memrik-Kalinovo Mennonite Church. During and after the Revolution this settlement suffered severely and disintegrated. In 1888 Molotschna Mennonites established the village of Alexandropol (30 farms), some 18 miles northeast of Memrik, near the station Ocheretino. The village prospered and had its own school and church buildings. Most of the settlers belonged to the Mennonite Brethren Church (see [[Alexandropol (Dnipropetrovsk, South Russia)|Alexandropol Mennonite Brethren Church]]). The settlers were in close contact with the Memrik settlement. | + | During the 1890s some Molotschna Mennonites purchased and settled on a part of a large estate some 12 miles (20 km) from the Memrik settlement, which they named Ossokino. In the center of the settlement they built their school, which also served on Sunday for worship. The settlers belonged to the [[Memrik and Kalinovo Mennonite Church (Ukraine)|Memrik-Kalinovo Mennonite Church]]. During and after the Revolution this settlement suffered severely and disintegrated. In 1888 Molotschna Mennonites established the village of Alexandropol (30 farms), some 18 miles northeast of Memrik, near the station Ocheretino. The village prospered and had its own school and church buildings. Most of the settlers belonged to the Mennonite Brethren Church (see [[Alexandropol (Dnipropetrovsk, South Russia)|Alexandropol Mennonite Brethren Church]]). The settlers were in close contact with the Memrik settlement. |

The Memrik settlement had to solve many economic problems in its early life. Grasshoppers, gophers, and other plagues caused great damage. The prices of the products were low. Originally the farmers followed the rotation cycle of wheat, feed, and summer fallow. They sowed mostly summer wheat, which was replaced by winter wheat around 1905. The "German Red" cattle became significant. Later Holsteins were introduced. Markets for agricultural products were found in Yuzovka (Stalino), Mariupol, [[Berdyansk (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Berdyansk]], etc. | The Memrik settlement had to solve many economic problems in its early life. Grasshoppers, gophers, and other plagues caused great damage. The prices of the products were low. Originally the farmers followed the rotation cycle of wheat, feed, and summer fallow. They sowed mostly summer wheat, which was replaced by winter wheat around 1905. The "German Red" cattle became significant. Later Holsteins were introduced. Markets for agricultural products were found in Yuzovka (Stalino), Mariupol, [[Berdyansk (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine)|Berdyansk]], etc. | ||

Revision as of 15:16, 30 September 2018

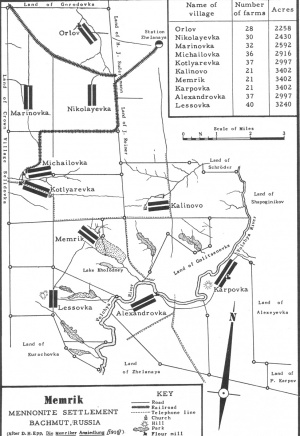

The Memrik Mennonite Settlement in Bachmut district, Ekaterinoskv province (Dnipropetrovsk), Russia (Ukraine), was founded in 1885 on the Volshya River, a tributary of the Samara, which in turn flows into the Dnieper. The settlement was located in the Don basin near the Catherine railroad, which connected it with the Sea of Azov. The next larger city was Yuzovka (later Stalino; still later Donetsk) some 20 miles (32 km) away.

The settlers came from the Halbstadt and the Gnadenfeld districts of the Molotschna settlement. A total of 32,400 acres of land were purchased from the noblemen Kotlyarevsky and Karpov in 1884 for the price of 600,000 rubles. A total of 221 families with 1,367 persons settled in ten villages on this land. In three of the villages each of the 21 farmers owned 162 acres, while in the remaining seven vilages, consisting of a total of 40 farms, each owned 81 acres. The latter were called "half farms." The names of the villages, later Russianized, were Alexanderhof (Alexandrovka), Bahndorf (Orlov), Ebental (Nikolayevka), Karpovka, Kotlyarevka, Marienort (Kalinovo), Memrik, Michaelsheim (Michailovka), Nordheim (Marinovka), and Waldeck (Lessowka).

The necessary qualifications of a settler were that "the head of the landless family conduct a quiet and moral life, be industrious and in possession of a wagon, plow, harrow, two horses, two cows, and the necessary means to establish a home." The land was mostly unbroken prairie. Although the quality of the land was excellent the settlers underwent the usual difficulties of pioneering. All settlers were expected to repay the loan and interest within 15 years to the Molotschna settlement, which sponsored the settlement. Originally Memrik was under the administration of the Molotschna settlement. Because the distance was over a hundred miles, Memrik tried to establish its own district or volost administration but failed. In 1888, contrary to the wishes of the settlers, it was incorporated in the neighboring Russian Golitzynov. The group was represented in this office by a settlement leader. The following served in this capacity: Heinrich Martins, Daniel Abrahams, Peter Dirks, Johann Köhn, and Julius Dörksen. In 1921 the settlement had its own volost office and administration for a short time. The settlement also had its own fire insurance agency, organized in 1901; Hermann Janzen, Jr., was its administrator for many years.

During the 1890s some Molotschna Mennonites purchased and settled on a part of a large estate some 12 miles (20 km) from the Memrik settlement, which they named Ossokino. In the center of the settlement they built their school, which also served on Sunday for worship. The settlers belonged to the Memrik-Kalinovo Mennonite Church. During and after the Revolution this settlement suffered severely and disintegrated. In 1888 Molotschna Mennonites established the village of Alexandropol (30 farms), some 18 miles northeast of Memrik, near the station Ocheretino. The village prospered and had its own school and church buildings. Most of the settlers belonged to the Mennonite Brethren Church (see Alexandropol Mennonite Brethren Church). The settlers were in close contact with the Memrik settlement.

The Memrik settlement had to solve many economic problems in its early life. Grasshoppers, gophers, and other plagues caused great damage. The prices of the products were low. Originally the farmers followed the rotation cycle of wheat, feed, and summer fallow. They sowed mostly summer wheat, which was replaced by winter wheat around 1905. The "German Red" cattle became significant. Later Holsteins were introduced. Markets for agricultural products were found in Yuzovka (Stalino), Mariupol, Berdyansk, etc.

Industry and commerce developed rapidly, particularly the milling industry. Steam mills were located in Bahndorf, Alexanderhof, Kotlyarevka, Karpovka, and near the station Zhelanaya (Heinrichs and Andres). One of the manufacturers of agricultural machinery was Julius Legin at Waldeck (started in 1895), who before World War I produced annually about 1,000 reapers, 600 plows, 300 fanning mills, etc., with an annual turnover of 150,000 rubles. Among the business people were H. Hamm of Zhelanaya and David Warkentin of Kalinovo. At times efforts were made to establish coal mines on the land owned by the Mennonites, but this never developed into large industry.

During the first years of the Memrik settlement elementary education was given in homes. Soon schools were erected in each of the villages. By 1910 most of the villages had modern larger school buildings made of brick, and residences for the teachers, both being modeled after the pattern established by the Molotschna Mennonites. Outstanding teachers were Peter Schellenberg, Jacob Koop, Jacob H. Janzen, Cornelius Unruh, and H. Goerz.

In addition to the elementary schools (six grades) there was also at Kotlyarevo a secondary school (Zentraschule) started in 1918 with D. P. Wiens and H. Goerz as teachers, which had to be closed after a few years. Another secondary school, established at Ebental in 1920, was gradually taken over by the state. Attendance became obligatory in 1930. As a rule the director was a non-Mennonite. Gradually all Mennonite teachers were forced to give up their positions or adjust to the Communist philosophy of education.

In 1914 the estimated property of the settlement (population of some 3,500) amounted to 11,145,000 rubles. During World War I some 240 young men were drafted into forestry and medical service. During the Revolution in 1918 Makhno and his bands inflicted great suffering on the settlement, murdering many inhabitants, and taking or destroying much property. During the struggle between the Soviet and White armies the Memrik settlement again suffered severely. Drought and starvation were severe. At last in 1922 some help came from America (Mennonite Central Committee). Conditions improved somewhat during the NEP period under the Soviets. Only some 30 families immigrated to Canada in 1923-1927. Very few managed to escape from Russia via Moscow in 1929.

In 1930 a great number of the farmers (kulaks) were sent to Siberia. During 1937-1938 some 240 men were exiled, none of whom returned nor was any information obtained about them. The remaining population was organized into three collective farms under the following names: Thalmann, Petrovky, and Karl Marx. The headquarters of these collectives were located in the former Mennonite Brethren church of Kotlyarevo.

During the outbreak of the German-Russian War in 1941 some young men were drafted. In September 1941 all men between 16 and 65 were sent to Asiatic Russia. On 5 October the remaining population received orders to appear at the station Zhelanaya, and from here they were also transported eastward. It is likely that they were sent to Kazakhstan in Siberia. When the German army reached Memrik there were only a few Mennonites left in the villages; Russian population had been moved into the villages. What happened to the villages in 1943 when the German army withdrew from Memrik was not known in the 1950s. The few Mennonites they found in Memrik were taken to Germany. Thus only a few of the Memrik Mennonites reached America after World War II.

Bibliography

Epp, David. H. Die Memriker Ansiedlung: zum 25-jährigen Bestehen derselben im Herbst 1910. Kalinowo, Post Shelannaja, Gouv. Jekaterinoslaw : D.J. Warkentin, 1910

Goerz, H. Memrik: Eine mennonitische Kolonie in Russland. Rosthern, SK : Echo-Verlag, 1954.

Goerz, H. Memrik: a Mennonite settlement in Russia. Winnipeg : Published jointly by CMBC Publications : Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society, 1997.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III, 74 f.

| Author(s) | Cornelius Krahn |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1957 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Krahn, Cornelius. "Memrik Mennonite Settlement (Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1957. Web. 21 Nov 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Memrik_Mennonite_Settlement_(Donetsk_Oblast,_Ukraine)&oldid=162165.

APA style

Krahn, Cornelius. (1957). Memrik Mennonite Settlement (Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 21 November 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Memrik_Mennonite_Settlement_(Donetsk_Oblast,_Ukraine)&oldid=162165.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 3, pp. 571-572. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.