Difference between revisions of "Melanchthon, Philipp (1497-1560)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

GameoAdmin (talk | contribs) (CSV import - 20130823) |

m |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

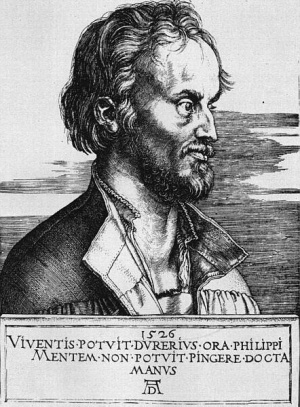

| − | [[File:melanchthon.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Philipp Melanchthon by Albrecht Dürer | + | [[File:melanchthon.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Philipp Melanchthon by Albrecht Dürer<br /> |

| + | Source: [http://www.dl.ket.org/webmuseum/wm/paint/auth/durer/portraits/index.htm WebMuseum, Paris]'']] | ||

| − | + | Philipp Melanchthon, (1497-1560), the German reformer, friend and co-worker of [[Luther, Martin (1483-1546)|Martin Luther]], the son of an armorer, George Schwarzerdt, whose wife was a niece of Johann Reuchlin. After his father's death he attended Latin school and at the age of 12 entered the University of Heidelberg, followed by the University of Tübingen in 1512, earning the M.A. degree there in 1514, which gave him the right to lecture. In 1518 Reuchlin recommended him as professor of Greek at the University of Wittenberg; on 29 August he delivered his inaugural address, which made a deep impression on Luther. A fast friendship was soon formed between them, with a lasting effect on the course of the Reformation. They complemented each other well. Luther, the religious genius and creative spirit, Melanchthon, the man of the pen, the keen scholar, who clothed Luther's ideas in scholarly form. Their friendship went through some difficult trials. Melanchthon was again and again offended by his friend's violent manner, severe judgment, and rough treatment of opponents; and Luther suffered under Melanchthon's timidity, hesitation, scruples, and fear. Melanchthon's last years were saddened by dogmatic strife brought on by his undecisive character, until death gently released him from the "rage of the theologians." | |

Melanchthon, generally a mild theologian, dealt with extraordinary harshness and increasing roughness with the [[Anabaptism|Anabaptists]]. He had not the least understanding for them. He saw in them only "irreligious fanatics and murderous revolutionaries, enemies of temporal government, however peaceful they may seem" (a letter to Myconius, February 1530), "a fiendish sect, which must not be tolerated" (a letter to Myconius, 31 October 1531). Therein lies deep tragedy, for in his ideas he was much closer to them than was [[Luther, Martin (1483-1546)|Luther]]. He held to freedom of the will, and sponsored the separation of religious and moral civil life (opinion to [[Philipp I, Landgrave of Hesse (1504-1567)|Philipp of Hesse]] in 1524), favored the reinstatement of the ban (church inspector's protocol), recognized in the immorality of the populace the damage done by the doctrine of justification, which was being used as a convenient bed of ease. He had temporary doubts concerning the validity of [[Infant Baptism|infant baptism]]. | Melanchthon, generally a mild theologian, dealt with extraordinary harshness and increasing roughness with the [[Anabaptism|Anabaptists]]. He had not the least understanding for them. He saw in them only "irreligious fanatics and murderous revolutionaries, enemies of temporal government, however peaceful they may seem" (a letter to Myconius, February 1530), "a fiendish sect, which must not be tolerated" (a letter to Myconius, 31 October 1531). Therein lies deep tragedy, for in his ideas he was much closer to them than was [[Luther, Martin (1483-1546)|Luther]]. He held to freedom of the will, and sponsored the separation of religious and moral civil life (opinion to [[Philipp I, Landgrave of Hesse (1504-1567)|Philipp of Hesse]] in 1524), favored the reinstatement of the ban (church inspector's protocol), recognized in the immorality of the populace the damage done by the doctrine of justification, which was being used as a convenient bed of ease. He had temporary doubts concerning the validity of [[Infant Baptism|infant baptism]]. | ||

Revision as of 08:06, 10 September 2013

Philipp Melanchthon, (1497-1560), the German reformer, friend and co-worker of Martin Luther, the son of an armorer, George Schwarzerdt, whose wife was a niece of Johann Reuchlin. After his father's death he attended Latin school and at the age of 12 entered the University of Heidelberg, followed by the University of Tübingen in 1512, earning the M.A. degree there in 1514, which gave him the right to lecture. In 1518 Reuchlin recommended him as professor of Greek at the University of Wittenberg; on 29 August he delivered his inaugural address, which made a deep impression on Luther. A fast friendship was soon formed between them, with a lasting effect on the course of the Reformation. They complemented each other well. Luther, the religious genius and creative spirit, Melanchthon, the man of the pen, the keen scholar, who clothed Luther's ideas in scholarly form. Their friendship went through some difficult trials. Melanchthon was again and again offended by his friend's violent manner, severe judgment, and rough treatment of opponents; and Luther suffered under Melanchthon's timidity, hesitation, scruples, and fear. Melanchthon's last years were saddened by dogmatic strife brought on by his undecisive character, until death gently released him from the "rage of the theologians."

Melanchthon, generally a mild theologian, dealt with extraordinary harshness and increasing roughness with the Anabaptists. He had not the least understanding for them. He saw in them only "irreligious fanatics and murderous revolutionaries, enemies of temporal government, however peaceful they may seem" (a letter to Myconius, February 1530), "a fiendish sect, which must not be tolerated" (a letter to Myconius, 31 October 1531). Therein lies deep tragedy, for in his ideas he was much closer to them than was Luther. He held to freedom of the will, and sponsored the separation of religious and moral civil life (opinion to Philipp of Hesse in 1524), favored the reinstatement of the ban (church inspector's protocol), recognized in the immorality of the populace the damage done by the doctrine of justification, which was being used as a convenient bed of ease. He had temporary doubts concerning the validity of infant baptism.

In mid-December 1527 the "Zwickau prophets," Nikolaus Storch, Thomas Drechsel, and Marcus Stübner, came to Wittenberg. They made a tremendous impression on Melanchthon. He wrote about them to Spalatin. Their "divine inspiration" he recognized as fanaticism, but to their objections to infant baptism he could find no answer until a letter from Luther (13 January 1522) freed him from his doubts. It is reasonable to assume that his later severity against the Anabaptists stemmed from his inability to come to terms decisively and effectively with the arguments of the Prophets. It is significant that his basic characterizations of Anabaptism, developed in later years, did not depart substantially from his analysis of the Prophets.

In 1522 Melanchthon became acquainted with Thomas Müntzer, who is said to have disputed with Melanchthon and Bugenhagen. From Alstedt Müntzer wrote at Easter in 1524 a letter to Melanchthon, in which he accused the Wittenbergers of neglecting the inner revelation, too much consideration of the weak, and servility to the princes. Further contacts between them have not been proved. He probably did not write the Historie von Thomas Münzer, which was long the principal source on Müntzer's activities in the Peasants' War (Brandt, 223).

At first Melanchthon took a tolerant attitude toward the Anabaptists and the Zwickau prophets, whom he identified with the former. In the letter to Frederick mentioned above he rejected the application of violent measures. Their "conventicle nature should not be stopped with violence, but with Scripture and judicio spiritualium hominum." But he soon changed his position; his attitude became increasingly harsh. Already in his Unterricht der Visitatoren of 1528 he placed every deviation from Lutheran doctrine under the punitive arm of temporal government as sedition. The mandate issued on 17 January 1528, by the Elector of Saxony, who was somewhat influenced in this instance by Melanchthon, threatened all who did not follow Lutheranism with loss of life and property.

In July 1527 Melanchthon was commissioned by the Elector to conduct an inspection (visitation) of the churches in Thuringia. Among his companions were Friedrich Myconius and Justus Menius. On this tour of inspection he encountered at least the teachings of those whom he called Anabaptists, if not the Anabaptists in person (letter to Camerarius 23 October 1527). He appended to his "Visitation Articles" a brief instruction to pastors on methods of effectively refuting Anabaptist arguments against infant baptism. His first major work against the Anabaptists, the Adversus anabaptistas Philippi Melanchthonis iudicium, is an elaboration of this basic argument. It was finished by 23 January 1528 and printed in April 1528. A German translation by Justus Jonas, Underricht Philip Melanchthon Wider die here der Wiederteuffer, appeared in October of the same year.

It was dedicated to Friedrich Pistorius, the abbot of a monastery in Nürnberg. It dealt with the sacraments, their number, and particularly with baptism, the baptism of John and the apostles, and infant baptism. He attempted to refute the "frightful, abominable, diabolical doctrine and error of the Anabaptists" and defended infant baptism on the grounds that it was the New Testament parallel to circumcision in the Old Testament.

Hardly two years' later he expressed himself definitely in favor of the death penalty for Anabaptists in the letter to Friedrich Myconius of February 1530:

"At first when I began to become acquainted with Storch and his following, to whom the whole family of Anabaptists owes its existence, I was possessed by a foolish tolerance. Others were also of the opinion that heretics are not to be destroyed with the sword. At that time Duke Frederick was violently angry with Storch, and if he had not been protected by us, the mad and thoroughly bad man would have been executed. Now I regret this lenience not a little. What disturbances, what heresies did he not stir up afterward? For you must think thus: As an armed race is said to have come forth from the teeth of a dragon, so have all these sects of Anabaptists and Zwinglians come forth from him. . . . All the Anabaptists, even if they are blameless in all other respects, reject some part or other of their civic duties. Though the matter in and for itself may be insignificant, yet at this time and in so many crises it is extremely dangerous. . . . Therefore it is my opinion concerning those who hold beliefs that are, to be sure, not seditious, but still obviously blasphemous, that the government is under obligation to kill them" (Wappler, Kursachsen, 13 f.).

On 18 January 1530 six Anabaptists were executed at Reinhardsbrunn in Saxony (see Kolb, Andreas). This execution evoked great excitement. Elector John now requested an opinion of the Wittenberg theologians. It was composed by Melanchthon and handed in at the end of October 1531 under the title, Gutachten an den Kurfürsten Johann von Sachsen. Following a lengthy introduction it said:

"In the matter of punishments distinctions must be made. For there are three kinds of Anabaptists: First the instigators and those who have made a second beginning; secondly followers and misled ones, who openly hold seditious beliefs, for instance, that it is unfitting to hold government office, that Christians must share their goods among each other, that a Christian should not swear an oath, not even to the government, that the churches should be reformed and the ungodly destroyed, that it is wrong to pay interest, and similar articles; in the third place there are many who erred because of lack of understanding, but could be persuaded to recant.

"The first class is to be killed with the sword, because they persisted contrary to the electoral mandate in holding meetings; for they have thereby shown themselves disobedient to the government. But the second class who hold obviously seditious articles of faith and persisted in them in spite of warning and instruction, should as revolutionaries also be put to death. . . . Finally those of the third class, who have erred because of ignorance, should be shown mercy after they have been instructed and have recanted their error, after they have made public confession and have been warned not to repeat the error. But if they do not desist from their error—'for many of them are possessed by the devil' —they should be expelled from the country, provided that no seditious beliefs or malicious intentions are found in them, or be punished by some other mild penalty" (Wappler, Kursachsen, 26 f.).

At the end of 1532 Luther and Melanchthon warned the council of Münster (Westphalia) and Bernhard Rothmann of the Zwinglians and fanatics. (See Germany.)

Three years later Melanchthon wrote his booklet, Etliche propositiones wider die lehr der Widerteuffer (erroneously dated 1528). It is a reply to Rothmann's Restitution, and the second edition of the same year bears the title, Wider das gotteslästerliche und schändliche Buch, so zu Münster im Druck neulich ist ausgegangen. In it he refutes the teaching of the Anabaptists of Münster concerning the violent erection of the kingdom of God, since the kingdom of Christ is spiritual, and concerning community of goods and polygamy. It is incomprehensible that he failed to distinguish between the peaceful and the revolutionary Anabaptists. "And it does no good," he writes, "to say that they are not all thus. But on the contrary, because the devil has torn them away from the true doctrine, as one devil is about as impious as another, and they are all together striving every moment against the kingdom of God and temporal order and rule, therefore one Anabaptist is like another, and the fact that they do not all make so much noise and innovation is due merely to lack of opportunity." In point 24 he calls the doctrine that "Christ did not take His flesh from the flesh of Mary, a terrible, abominable blasphemy. In it one can see that they conceal other poison and blasphemy concerning Christ."

From Melanchthon a different verdict might have been expected concerning the Anabaptists. He had far better opportunity to become acquainted with them. On 1 December 1535 he took part in a long cross-examination of Anabaptists imprisoned in Jena. It lasted several days. Melanchthon and his colleagues used all their ingenuity and great learning to convince the prisoners of their error. Results were meager. In a report to the Elector of Saxony (Bericht an den Kurfürsten Johann von Sachsen) on 19 January 1536, he wrote "Against the obstinate it is necessary to apply serious punishment. And even some may not be malicious in other respects, nevertheless we must resist the shameful sect, in which there is so much horrible and shameful error" (Wappler, Thüringen, 149). Several days later, the Anabaptists in Jena, who remained true to their faith, were executed.

In the letter to the elector cited above, Melanchthon urged the publication of an official writing which would reveal what "coarse, seditious, shameful, and harmful articles the Anabaptists hold." He was commissioned to write it. On 10 April 1536 a new mandate against the Anabaptists was issued for Saxony, using the executed Anabaptists as a warning to others. The following are the main articles of their faith, as he states them, by means of which they deceived the simple folk in body and soul: (1) Christians should not and can not be in an office of government, which take the sword; (2) Christians should have no other government over them than the preachers of the Gospel; (3) Christians are forbidden to swear an oath, and to swear is sin; (4) Christians are obliged to give their possessions to the common good, and shall have no property; (5) If one partner in a marriage is a true believer and the other is not, then the believer may leave the unbeliever and court another, merely on account of his faith; (6) That infant baptism is wrong; (7) Infants have no sin; "original sin," socalled, is not in fact sin; (8) That alone is sin which man of his own free will commits.

In addition Melanchthon wrote a booklet that was by electoral command to be given to every pastor in the electorate with the obligation to read it from the pulpit every third Sunday. Its title was Verlegung etlicher unchristlicher Artikel, welche die Wiederteuffer fürgeben. This booklet of instruction appeared in two editions in 1536. It contains very sharp language for the gentle reformer. He called Anabaptism a "horrible devilish sect." He maintained that the government was obliged "to resist and punish such shameful, murderous doctrine, since it teaches only revolt, theft and murder, besides immorality and adultery"; events at Münster proved this, he held. He called them Manichaeans and expressed the hope that like them, they would not increase or remain long. The Anabaptist sect, he said, was simply a diabolical deception, which must be punished with force and wiped out.—What the Anabaptists thought of this booklet is shown by the statement of a prisoner, that there was not a true word in it (Wappler, Inquisition, 78).

In May 1536 Philipp of Hesse also requested an opinion of the Wittenberg theologians, for advice in dealing with the Anabaptists imprisoned in his realm. The opinion was delivered on 5 June 1536 (see Punishment). It was composed by Melanchthon and signed by Luther, Bugenhagen, and Cruciger. The title was Das Weltliche Oberkeitt den Widertaufferen mit leiblicher straff zu weren schuldig sey. (One edition of the pamphlet bore the subtitle: Melanchthonis Iudicium: Ob christliche Fürsten schuldig sind, der Wiedertäufer unchristlicher Sekte mit leiblicher Strafe und mit dem Schwert zu wehren.) This booklet stated most definitely that Anabaptists were to be punished with the sword.

Also in a letter to Henry VIII of England, 25 September 1538, Melanchthon sponsored the severest punishment for the Anabaptists. In his opinion of 5 February 1539, concerning religious conditions in the duchy of Jülich, he cautioned that "there is much vermin of Anabaptists there" (Rembert, Wiedertäiufer, 267).

The Anabaptist question occupied Melanchthon once more at the disputation of Worms in 1557 in the summarizing statement which he drew up, called Prozess, wie es soll gehalten werden mit den Wiedertäufern. His attitude had not grown more lenient. As seditionists and blasphemers, he said, they should be killed with the sword, according to Leviticus 24. Two years later, in 1559, when the question was asked: Does a pious government do wrong in killing Anabaptists who cling to their terrible errors? he replied with lengthy argument: If they are obstinate and stubbornly persist in their error, they may be killed as revolutionaries. In this final declaration of Melanchthon against the Anabaptists (entitled Ob fromme Obrigkeiten unrecht tun, wenn sie an schrecklichen Irrtümern festhaltende Wiedertäiufer töten) he contended that on the basis of natural law the Anabaptists should be killed. (C.R. IX, 1002-4.)

One can only lament this verdict of Melanchthon's, which has been fraught with such dire consequences in church history. Two hundred years were to pass before religious toleration was given its due.

Bibliography

Clemen, O. Melanchthons Briefwechsel, Supplemented Melanchthoniana. Leipzig, 1926.

Corpus Reformatorum I, III, IV, IX.

Döllinger, Johann von. Die Reformation : ihre innere Entwicklung und ihre Wirkungen im Umfange des Lutherischen Bekenntnisses. Regensburg : G. Joseph Manz, 1846-1848.

Ellinger, Georg. Philipp Melanchthon, Ein Lebensbild. Berlin: R. Gaertner, 1902.

Engelland, Hans. Melanchthon, Glauben und Handeln. München: Kaiser, 1931.

Gussmann, Wilhelm. Quellen und Forschungen zur Geschichte des Augsburgischen Bekenntnisses. Leipzig, 1911.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. III, 66-69.

Nippold, Friedrich. Was giebt den heutigen Universitäten Recht und Pflicht zu einer Melanthon-Feier?: akademische Festrede; gehalten am 16. Februar 1897. Bern: Schmid & Francke, 1897.

Oyer, J. S. "The Writings of Melanchthon Against the Anabaptists." Mennonite Quarterly Review 26 (1952): 259-279.

Paulus, Nikolaus. Protestantismus und Toleranz im 16th Jahrhundert. Freiburg i. B.: Herder, 1911.

Richard, James William Philipp Melanchthon. NY, 1907.

Schmidt, Carl. Philipp Melanchthon: Leben und ausgewählte Schriften. Eberfeld: Friderichs, 1861.

Stupperich, Robert. "Melanchthon und die Täufer." Kerugma und Dogma III (1957): 150-170.

Wappler, Paul. Inquisition und Ketzerprozesse in Zwickau zur Reformationszeit: Dargestellt im Zusammenhang mit der Entwicklung der Ansichten Luthers und Melanchthons über Glaubens- und Gewissensfreiheit. Leipzig : M. Heinsius, 1908.

Wappler, Paul. Die Stellung Kursachsens und des Landgrafen Philipp von Hessen zur Täuferbewegung. Münster i. W. : Druck und Verlag der Aschendorffschen Buchh., 1910.

Wappler, Paul, ed.. Die Täuferbewegung in Thüringen von 1526-1584. Jena : G. Fischer, 1913.

Wiswedel, W. W. and R. Friedmann."The Anabaptists Answer Melanchthon." Mennonite Quarterly Review 29 (1955): 212-231.

| Author(s) | Christian Neff |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1957 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Neff, Christian. "Melanchthon, Philipp (1497-1560)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1957. Web. 16 Apr 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Melanchthon,_Philipp_(1497-1560)&oldid=101435.

APA style

Neff, Christian. (1957). Melanchthon, Philipp (1497-1560). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 16 April 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Melanchthon,_Philipp_(1497-1560)&oldid=101435.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 3, pp. 562-564. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.