Difference between revisions of "Humanism"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (Text replace - "</em><em>" to "") |

m (Text replace - "<em>Mennonite Quarterly Review</em>" to "''Mennonite Quarterly Review''") |

||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. <em>Mennonitisches Lexikon</em>, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. II, 365-368. | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. <em>Mennonitisches Lexikon</em>, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. II, 365-368. | ||

| − | Kreider, Robert. "Anabaptism and Humanism: an Inquiry Into the Relationship of Humanism to the Evangelical Anabaptists." | + | Kreider, Robert. "Anabaptism and Humanism: an Inquiry Into the Relationship of Humanism to the Evangelical Anabaptists." ''Mennonite Quarterly Review'' 26 (1952): 123-41. |

<strong>For discussions of Erasmian influence on the Anabaptists, see: </strong> | <strong>For discussions of Erasmian influence on the Anabaptists, see: </strong> | ||

| − | Augustijn, Cornelis. "Erasmus and Menno Simons." | + | Augustijn, Cornelis. "Erasmus and Menno Simons." ''Mennonite Quarterly Review'' 60 (1986): 197-208, |

| − | Davis, Kenneth R. "Erasmus as a Progenitor of Anabaptist Theology and Piety." | + | Davis, Kenneth R. "Erasmus as a Progenitor of Anabaptist Theology and Piety." ''Mennonite Quarterly Review'' 47 (1973): 163-78. |

| − | Hall, Thor. "Possibilities of Erasmian Influence on Denck and Hubmaier in Their Views of Freedom of the Will." | + | Hall, Thor. "Possibilities of Erasmian Influence on Denck and Hubmaier in Their Views of Freedom of the Will." ''Mennonite Quarterly Review'' 35 (1961): 149-70. |

Harder, Leland, ed. <em>The Sources of Swiss Anabaptism: the Grebel Letters and Related Documents</em>, Classics of the Radical Reformation, vol. 4. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1985. | Harder, Leland, ed. <em>The Sources of Swiss Anabaptism: the Grebel Letters and Related Documents</em>, Classics of the Radical Reformation, vol. 4. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1985. | ||

| − | Schrag, Dale R. "Erasmian and Grebelian Pacifism: Consistency or Contradiction?" | + | Schrag, Dale R. "Erasmian and Grebelian Pacifism: Consistency or Contradiction?" ''Mennonite Quarterly Review'' 62 (1988): 431-454. |

{{GAMEO_footer|hp=Vol. 2, pp. 841-843; v. 5, pp. 399-400|date=1990|a1_last=Händiges|a1_first=Emil|a2_last=Schrag|a2_first=Dale R.}} | {{GAMEO_footer|hp=Vol. 2, pp. 841-843; v. 5, pp. 399-400|date=1990|a1_last=Händiges|a1_first=Emil|a2_last=Schrag|a2_first=Dale R.}} | ||

Revision as of 23:06, 15 January 2017

1956 Article

Humanism, since the middle of the 15th century is the designation of an intellectual movement, which in many respects prepared the way for the Reformation and in contrast to medieval theology placed man in his natural and intellectual development in the foreground, sought to free him from all hierarchical and scholastic restraints and endeavored to build a new culture and Weltanschauung on the foundation of the purely human.

As the basis of education Humanism valued the "humanities" (studia humaniora), especially as they were presented in the works of classical antiquity and to whose content scholars devoted themselves with a new zeal. To be sure, the writings of the Greeks and Romans were not entirely neglected in medieval times; Aristotle indeed had a profound effect particularly on formal education; but on the whole they were only of secondary importance, and science remained dependent upon the church and philosophy was regarded as the "handmaid of theology."

The second half of the 15th century brought with it a fundamental change in this respect. Its point of orientation the Humanistic movement took from Italy. At the time of the "Council of Union" (1439) important Greek scholars from the Orient had come to Florence and exerted their influence on the western world. After the conquest of Constantinople by the Turks (1453) many Greeks fled to Italy. Through their influence first in the field of art, a conscious connection was made with antiquity which was united in the Renaissance with the new feeling of life of the greatest Italian painters; in philosophy Humanism triumphed as the new intellectual movement.

The principal nurseries of this movement were the princely courts of the Medicis in Florence; but the new spirit also penetrated into the highest circles of the hierarchy and the Curia at Rome. Classical learning was accompanied by antique heathenism and a refined syncretism in the secularized church, and occasionally could be heard the pulpit greeting, "Beloved in Plato." For Christianity the Italian Humanists had only a historical or aesthetic interest, in so far as they were not completely indifferent or actually hostile to it.

Much deeper was the development of the Humanistic movement in the countries north of the Alps, where it achieved its greatest significance and where it found a soil prepared for its coming in the schools endowed by Gerhard Groote of the Brethren of the Common Life, especially at Deventer in the Netherlands and later at Schlettstadt in Alsace (Jakob Wimpfeling). Humanism reached its decisive influence when it passed from the Latin schools into the universities and was zealously cultivated there: first in Vienna (Celtes), then in Basel, Freiburg, Heidelberg (Agricola), Tübingen, Ingolstadt, Erfurt (Muth), Leipzig, etc. Everywhere a new spirit of research awoke, and through the invention of the art of printing about 1450 the Humanistic ideas found rapid dissemination, especially among the educated classes, the patricians in the cities (Augsburg, Nürnberg, Strasbourg), as well as the nobility of Germany (Ulrich von Hütten, Franz von Sickingen).

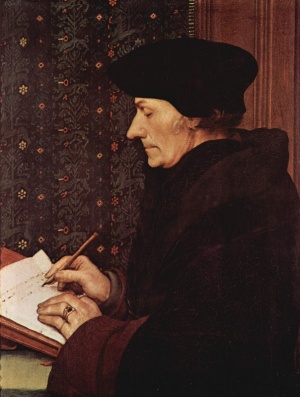

The cry, "Back to the sources!" was now applied not only to the study of the old classics; it became the stimulus for the eager study of the original text of the Bible and the writings of the Church Fathers, especially of Augustine. The outstanding representatives and leaders of Humanism were Johann Reuchlin (d. 1522) and Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam (d. 1536). Reuchlin's most meritorious service was in the field of the original language of the Old Testament; his Hebrew grammar was long the only textbook of this language. Erasmus published the first critical edition of the New Testament in 1516; the second edition (of 1519) was used by Luther as the basis of his translation. Philipp Melanchthon succeeded in harmonizing the rich Humanistic intellectual training of the time with the new theology filled with Luther's gospel and making them serve the purposes of the Reformation. Luther himself remained spiritually aloof from Humanism; he felt the difference in spirit. He violently attacked the dominating influence of Aristotle in theology. "From Aristotle back to Paul and Augustine!" was the watchword with which he led the new "Wittenberg theology" into sound paths.

The positive effect of Humanism came to the surface in the open break with the former world of culture. The reign of Scholasticism fell, and science was freed from the guardianship of the church. From serfdom the people and the individual awoke to maturity, to a clearer awareness of self and to personal responsibility, also in matters of faith. Through occupation with religious questions and through the reading of religious pamphlets and books a new lay piety arose. In opposition to the claims of Rome a new national feeling grew stronger. In rude popular wit and biting satire the intrigues and the monastic narrowness of the priesthood were uncovered and mocked. Against the intolerance of the obscurantists a sharp pen war was carried on. The cry for a reform of the church in its leadership and laity grew more common and could no longer be suppressed. Through all of this, Humanism helped to pave the way for religious renewal.

But the negative side of Humanism must not be overlooked. Humanism was not able to penetrate the core of the Gospel. It was more concerned with the education of the spirit than with a renewal of the heart. It remained uninterested and politely indifferent to the actual questions of salvation. In addition to morally outstanding representatives who led an exemplary life, there were others who felt themselves above all moral restraints. Many Humanists rejected the absoluteness of the Christian religion and placed the ethics of Plato and Cicero or the Stoics on the same plane as Jesus' Sermon on the Mount. Syncretism and Pelagianism, indeed often heathen superstition (magic, alchemy, fear of witches), were not lacking. Powers much deeper than and very different from those shown by Humanism were required to produce an inward renewal and transformation of religious and spiritual conditions among the Western peoples. They were not found in Humanism, but in the new comprehension of sin and salvation of the Reformation with its cardinal question, "How can I acquire a merciful God?" Humanism could only serve by preparing the way.

As Humanism in some respects was in general of service to the Reformation, it also in a certain sense helped to break a path for the Anabaptist movement. There was, however, no close connection between Humanism and Anabaptism. But in the field of formal scientific training many an Anabaptist, like Conrad Grebel, Felix Manz, Balthasar Hubmaier, Hans Denck, etc., owed a good share of his sound education to Humanism.

Conrad Grebel acquired a comprehensive knowledge of Latin, Greek, and Hebrew during his student years in Vienna, Paris, and Basel. Theology was still remote from his interests, and yet "it would be an error to reckon him as one of the adherents of Humanism antagonistic to Christianity." His fundamental religious views, which he put into reality in the founding of the brotherhood in Zürich, were rooted in his later conversion and were determined only by the words of the Holy Scriptures.

The same is true of Felix Manz. He had pursued Humanistic studies in Basel and had a thorough mastery of the classical languages. With Zwingli he read the Old Testament in Hebrew; his expositions of the Bible at their meetings are based on the original text of the New Testament. But his preaching showed no trace of Humanistic influence, but was thoroughly Biblical and theologically orientated.

Hubmaier had a brilliant Humanistic education at his command, the foundation of which had already been laid in the Latin school in Augsburg. At the university of Freiburg he completed it with deep seriousness. Among his teachers Dr. Eck, Luther's later opponent, exerted the greatest influence on him. Hubmaier speaks of Eck with gratitude. "It is wonderful to say," he says, "with what care and eagerness I took up the philosophical ideas, how carefully I listened to my teacher and how zealously I took down his lectures—an industrious reader, an untiring listener, and a busy teacher of the other hearers. So I won the master's degree with the highest praise . . . . What progress I made is attested by my learned lectures, my sermons before the people, and my scholastic exercises" (Loserth, 15). Hubmaier's later works showed a comprehensive knowledge of patristic literature. Thus in his booklet, Der uralten und gar neuen Lehrer Urteil of 1526, he based his teaching on baptism upon the teachings found in Origen, Basil, Athanasius, Tertullian, Jerome, Cyril, Theophylactus, Eusebius, the Corpus juris Canonica; but the more recent authorities were also used by him, in the first place the great Humanist Erasmus (Loserth, 143 ff.). But even though his opponents marveled at his classical education, Fabri called him a "man of select spirit and outstanding education," and von Watt a "highly eloquent and in a high degree humanistically educated man" (eloqucntissimum et humanis-simum virum), for Hubmaier all of this was only of formal significance. Humanism furnished him only with the weapons for his fight of faith. His religious life was rooted in his experience of salvation in Christ; the "touchstone" by which he tested all things and on which he based his teaching was the Bible.

Hans Denck also owed his scholarly preparation largely to Humanism; in religious matters, however, he went his own way. Nevertheless his teaching on the freedom of the will, his demand for unconditional liberty of faith and conscience, and his principle of tolerance showed the influence of Humanism. In Basel he got into close touch with Oecolampadius and applied himself to the study of the classical languages, especially Hebrew. He was also one of the close circle of students, with whom Erasmus associated. But there is no evidence of any deep influence of that great Humanist upon Denck. A splendid product of his knowledge of Hebrew was the translation of the Old Testament Prophets from the Hebrew, which Denck and Ludwig Haetzer together published in Worms in April 1527. The content of Denck's sensitive contemplative ideas was derived from Christian mysticism, especially from Tauler's sermons and from the Deutsche Theologie, which Luther had published. Denck's doctrine of regeneration and his requirement of discipleship of Jesus in daily life was far above the moral average of his contemporaries.

The relationship of Anabaptism to Humanism may be summarized as follows:

In common with Humanism Anabaptism was characterized by a fearless critique of the traditional ecclesiastical system, a break with the medieval hierarchical concept, a demand for a completely new order in church conditions, a return to the sources of original Christianity, the responsibility of the individual for his own decisions, the demand for complete liberty of faith and conscience and the principle of religious tolerance.

But the ways by which these aims were to be accomplished and the fundamental temper in which it was done were different. Humanism hoped to be able to attain them by humanitarian means; Anabaptism insisted on a renewal of heart, rebirth, and discipleship in daily life. Humanism was basically anthropocentric, Anabaptism Christocentric. To Humanism the actual questions of salvation were unimportant; to Anabaptism the doctrine of salvation had the key position. Humanism regarded the Scriptures as a historic document; Anabaptism held them as the only guide for faith and conduct. Humanism sought the truth by way of intellectual understanding; Anabaptism looked for it only through divine revelation. To Humanism Christ was a teacher and example among many others; to Anabaptism He was the Son of God and the only medium of salvation. Humanism was concerned with the creation of a new culture; Anabaptism with the realization of the kingdom of God, including the relations of earthly life. To Humanism knowledge was an end in itself; to Anabaptism it was merely a tool of preparation. Humanism promoted the feeling of life and aesthetic enjoyment of life; Anabaptism demanded self-denial and willingness to bear the cross to the point of martyrdom. In many of its representatives Humanism taught that what pleases was permissible; Anabaptism required fulfillment of the divine commands in the obedience of faith. Humanism pursued a philanthropic ideal and created an elite of the spirit; Anabaptism sought a reconciliation of differences in love to the brethren. Humanism was generally indifferent to the Christian ordinances; Anabaptism recognized in the ordinances of Christ and the apostles a means for the realization of the New Testament church.

In an objective evaluation of given relationships and existing influences and in a critical weighing of inner conflicts, collective Protestantism and with it Anabaptism must not fail to recognize how much it owes to Humanism, especially in its German interpretation. In its positive and negative effects it was an important factor in the historical development of church conditions and in its transition from an old to a new era. -- Emil Händiges

1990 Article

To consider the term humanism in an Anabaptist and Mennonite context is to confront at the very outset a significant definitional problem. In the 20th century the term has come to imply a world view that is uncompromisingly and exclusively secular and non-religious, a view that has been reinforced both by the selfproclaimed "humanists" and their Fundamentalist Christian detractors. The Humanist Manifesto II (1973) openly denies the existence or significance of a supernatural power; the Fundamentalists have equated humanism, often with the modifier secular added, with atheism and reduced the term to a kind of catchword for all manner of evil in the modern world. If this radically secular definition of humanism is accepted, then Christian Humanism is a self-contradictory term and then humanism can only be seen as antithetical to the most fundamental tenets of the Mennonite faith.

Even a cursory review of the origins of the term, however, reveals the inadequacies of this oversimplified 20th century definition. When applied to the 16th century, for example, the term humanism carries a markedly different connotation. Paul Oskar Kristeller, perhaps the greatest contemporary scholar of Renaissance humanism, defines the term very narrowly as deriving from the humanista, the professional teachers of the studia humanitatis (the "studies befitting a human being" or the "study of the humanities"). Since the Renaissance humanists were unquestionably more enamored of the excellence and dignity of mankind than had generally been the case during the Middle Ages, early historians of the Renaissance, for example, Jacob Burckhardt (1818-97), emphasized, indeed overemphasized, the secular nature of Renaissance humanism. More recent historical scholarship, however, has demonstrated that such an image of an irreligious, or even non-religious, Renaissance humanism is simply not supported by the evidence. Lewis Spitz, The religious renaissance of the German humanists (1963), established without question the religious--even devout--nature of humanism in the north of Europe. Charles Trinkaus, In our image and likeness: humanity and divinity in Italian humanist thought (1970), similarly shattered the myth of a pagan Italian Renaissance humanism. The best historical evidence, therefore, suggests that the Renaissance humanists were, in virtually all cases, Christian; indeed, in many of the most outstanding cases, they were deeply Christian. This is especially true with the "Prince of the Humanists," Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466?-1536). Though early 20th-century historians emphasized a highly rational, largely secular Erasmus, the overwhelming consensus of modern scholarship portrays a profoundly Christian Erasmus. In the 16th century, then, the term Christian humanist is more self-evident than paradoxical.

This distinction is critical, because it has long been recognized that a good number (e.g., Conrad Grebel, Hans Denck) of the 16th-century Anabaptists received "humanistic" educations and moved in humanist circles. They clearly read (and in a few cases may even have visited) Erasmus. Moreover, there are a number of apparent similarities between the agenda of 16th-century humanism and the theology of the Anabaptists. The humanists were committed to returning to the pure sources of classical and Christian civilization; their rallying cry was ad fontes ("to the sources"); they looked to those sources for models of behavior, exemplars after whom to pattern their own lives. Anabaptists likewise sought to restore primitive Christianity: their commitment was to the restitution of 1st-century Christianity, not to the reformation of 16th-century Christianity; and they found their exemplar in the person of Jesus Christ. The humanists emphasized human freedom and dignity; the Anabaptists, in contrast to all the major Protestant movements in the 16th century, denied the doctrine of predestination and insisted on an anthropology of free will. And, for the humanists, behavior--not belief--was the measure of a man; similarly, for the Anabaptists, discipleship (i.e., behavior)--not belief--was the key to salvation.

An earlier generation of Mennonite historians, seeing the similarities but convinced that humanism and Christianity were mutually exclusive categories, simply denied the possibility of influence. Thus Harold S. Bender, for example, could claim that Conrad Grebel's humanist period "made no evident contribution to his religious life or thinking". But in light of the research of Kristeller, Spitz, Trinkaus, and others, we can acknowledge the reality of Christian humanism and affirm its role as one of the formative influences which shaped 16th century Anabaptism. -- Dale R. Schrag

Bibliography

For the original publication of the Humanist Manifesto II, see:

The Humanist 33 (September-October 1973): 4-9.

For a thorough and precise discussion of the term "Humanism," see:

Giustiniani, Vito R. "Homo, Humanus, and the Meanings of 'Humanism."' Journal of the History of Ideas 46 (April-June 1985): 167-95.

For discussions of the nature of Renaissance humanism, see:

Clemen, O. "Humanismus in Religion." Die Religion in Geschichte and Gegenwart, 2nd. ed., 5 vols. Tübingen: Mohr, 1927-1932.

Hermelink, H. Die religiösen Reformbestrebungen des deutschen Humanismus. Tübingen, 1907.

Kristeller, Paul Oskar. Renaissance Thought: the Classic, Scholastic, and Humanistic Strains. New York: Harper and Row, 1961: esp. 110-12, and other works by Kristeller.

Loofs, Friedrich. Leitfaden zum Studium der Dogmengeschichte. Halle: Niemeyer, 1951.

Spitz, Lewis. The Religious Renaissance of the German Humanists. Cambridge, MA: Harvard, 1963.

Springer, Anton. Handbuch der Kunstgeschichte: Die Kunst der Renaissance in Italien, Bd. 3. Leipzig: A. Kröner, 1923-1929.

Trinkaus, Charles. In Our Image and Likeness: Humanity and Divinity in Italian Humanist Thought, 2 vols. Chicago: U. of Chicago Press, 1970.

Trinkaus, Charles. The Scope of Renaissance Humanism. Ann Arbor, MI: U. of Michigan Press, 1983.

Windelband, W. A History of Philosophy. 2nd ed., N.Y., 1901.

Wuttke, Adolf. Handbuch der Christliche Sittenlehre. 3rd ed., Leipzig, 1874.

On Anabaptism and humanism generally, see:

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. II, 365-368.

Kreider, Robert. "Anabaptism and Humanism: an Inquiry Into the Relationship of Humanism to the Evangelical Anabaptists." Mennonite Quarterly Review 26 (1952): 123-41.

For discussions of Erasmian influence on the Anabaptists, see:

Augustijn, Cornelis. "Erasmus and Menno Simons." Mennonite Quarterly Review 60 (1986): 197-208,

Davis, Kenneth R. "Erasmus as a Progenitor of Anabaptist Theology and Piety." Mennonite Quarterly Review 47 (1973): 163-78.

Hall, Thor. "Possibilities of Erasmian Influence on Denck and Hubmaier in Their Views of Freedom of the Will." Mennonite Quarterly Review 35 (1961): 149-70.

Harder, Leland, ed. The Sources of Swiss Anabaptism: the Grebel Letters and Related Documents, Classics of the Radical Reformation, vol. 4. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1985.

Schrag, Dale R. "Erasmian and Grebelian Pacifism: Consistency or Contradiction?" Mennonite Quarterly Review 62 (1988): 431-454.

| Author(s) | Emil Händiges |

|---|---|

| Dale R. Schrag | |

| Date Published | 1990 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Händiges, Emil and Dale R. Schrag. "Humanism." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1990. Web. 16 Apr 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Humanism&oldid=143604.

APA style

Händiges, Emil and Dale R. Schrag. (1990). Humanism. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 16 April 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Humanism&oldid=143604.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 841-843; v. 5, pp. 399-400. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.