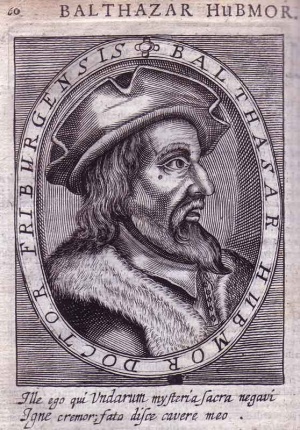

Hubmaier, Balthasar (1480?-1528)

Scan provided by the Mennonite Archives of Ontario.

Introduction

Balthasar Hubmaier (Huebmör), an Anabaptist leader 1525-1528, particularly in Moravia, where he was the head of a large congregation 1526-1528, outstanding for the number and importance of his writings, but of no great permanent influence on the later Anabaptist-Mennonite movement, since he diverged from the main line of Anabaptists on the question of nonresistance, and his group of "Schwertler" did not survive his death more than one or two years. He has been variously evaluated. Some have judged him solely by his attitude in the confusion of the Peasants' War; others see him only in his reformatory work in the church. The Baptists in general have viewed him as their great hero among the Anabaptists and celebrated the 400th anniversary of his martyrdom with a special observance in Vienna in 1928. The following presentation, which is based on an objective examination of his works, and which does not leave his opponents out of consideration, will show that he did not advocate radical views, either in the realm of society or the church. His motto was "The truth is immortal." He strove toward it. The truth, he says, occasionally lets itself be captured, yea lashed, crowned, crucified, and buried, but on the third day it will rise victorious, and reign in triumph. This striving of his for the truth becomes evident in his course in life and his teaching, and for it he went to his death with courage.

Hubmaier's Life and Teachings

The date of Balthasar Hubmaier's birth is not known. It is assumed that it was in the early 1480's. His native town was Friedberg near Augsburg. His contemporaries called him Pacimontanus after the former, or Augustanus after the latter. He called himself usually Huebmör (as the Geschicht-Buch spells it) or Huebmör von Friedberg. He probably received his early education at home; he attended the Latin school in Augsburg. To his contemporaries we owe a description of his appearance and his personality. He was of short stature and swarthy; when he is described as being proud, it must not be overlooked that this description was given by an opponent.

At Easter 1503 Hubmaier matriculated at the University of Freiburg, Germany, where Eck, later the opponent of Luther, acquired powerful influence over him, and praised him for his rapid progress. In genuine devotion he pursued his theological studies. Lack of funds compelled him to accept a position as a schoolteacher (1507) in Schaffhausen, but he soon returned to Freiburg, took his baccalaureate in 1510, and was ordained to the priesthood. When his teacher Eck went to Ingolstadt, he followed; and there he received the honor of a licentiate, then of a Doctor of Theology. In 1515 he was prorector of the university, and a year later, because of his pulpit eloquence, he was given the honorable position of pastor and chaplain in the ancient cathedral in Regensburg. The populace of Regensburg was involved in a dispute of long standing with the Jews; in it Hubmaier took an active part. It ended in the expulsion of the Jews and the razing of their synagogue; in its place a chapel "zur schönen Maria" was erected, where according to the credulous public there was no lack of miracles; this led to a great concourse of pilgrims and rich gifts for a church. Hubmaier, as the first chaplain of the chapel, kept a record of the supposed miracles. The pilgrimages to Regensburg caused some excitement which resulted in some coarse abuses, for which Hubmaier blamed the eccentric character of the pilgrims.

These events in particular, then also the insecurity of his position, led Hubmaier to accept a pastorate in Hapsburg territory, in the town of Waldshut in Breisgau, situated at an important ford in the Rhine. He preached his first sermon there in the spring of 1521. He was still loyal to his Catholic faith when the Reformation movement had made itself felt in all parts of the Holy Roman Empire, punctiliously observing all the customs of the church, and won the complete confidence of his congregation. But by the summer of 1522 he had begun to change. He studied Luther's writings, made connections with the friends of the Reformation, and engaged in a study of the Pauline epistles. Soon a new call to the Regensburg church reached him and he accepted. But there was already some evidence of his leanings toward the new doctrine. His position became equivocal, and even before the year contracted for had expired he returned to his pastorate at Waldshut, which had been held open for him.

The change in his religious convictions, which drew Hubmaier in the direction of the Swiss rather than to Luther, he now expressed without hesitation. He opened correspondence with the Swiss reformers and in 1523 discussed with Zwingli the passages of Scripture on baptism. "Then Zwingli agreed with me, that children should not be baptized before they are instructed in the faith." Then he began some innovations in Waldshut. Of decisive importance was his participation in the disputation held by order of the Zürich council in the city hall on 26-28 October 1523. Here Hubmaier expressed himself sharply in opposition to the abuses in the Mass and the worship of images. He declared that the Bible alone must decide such questions; the Mass is not a sacrifice, but a proclamation of Christ's testament, which commemorates His bitter suffering and His sacrifice of His life; as a sacrificial offering the Mass benefits neither the living nor the dead. "Just as I cannot believe for another, neither can I hold a Mass for another.' Concerning the worship of images he cited the Scripture that a carved or graven image is an abomination to God.

As a pulpit orator Hubmaier, received great applause. His attitude in Zürich met with the disapproval of the Austrian government, which painfully watched the progress of the new ecclesiastical movement in its outlying lands. But Hubmaier continued on his way. In the spirit of Zwingli he delivered his 18 Schlussreden concerning the Christian life, which he hoped would win the clergy of Waldshut. The citizenry was already on his side. His connections extended over a large portion of South Germany. But the Catholic party was not idle. Sharply worded letters from secular as well as spiritual authorities demanded the removal of Hubmaier. So much the more expressly he worked for the Reformation in Waldshut, conducting the religious service in German, and abolishing the laws on fasting and the celibacy. He married Elisabeth Hügeline, the daughter of a citizen of Reichenau, who willingly and bravely shared his later lot. All the attempts of the government to restore the old order of things in Waldshut failed; it therefore decided to compel the city to obedience by the use of force. Then Hubmaier requested his own dismissal.

On 1 September 1524, he left Waldshut for Schaffhausen. But he was not safe there either. "Very soon," he wrote, "warnings were brought to me that I was to be arrested." The government opened negotiations with Switzerland, but since Hubmaier had settled in Schaffhausen "in der Freiung" the city refused to deliver him into the hands of Austria. In three written Erbietungen he declared himself ready to defend what he had been teaching for two years; and in order to defend himself against the charge of heresy he wrote his booklet Von Ketzern and ihren Verbrennern. His opponents were meanwhile incessantly working to have him extradited. Not feeling secure "in der Freiung" he returned to Waldshut. The city, threatened with a heavy fine by the government, and hoping to find outside assistance, was now in open opposition to the government. Hubmaier became the soul of its resistance, and now completed the Reformation of the church in Waldshut.

He still adhered to Zwingli's party. But Zwingli was already meeting opposition in Zürich; his opponents accused him of not holding earnestly to the cause, and wanted him to separate from the ungodly and to gather a brotherhood of the true church of God. The leaders among his opponents were Conrad Grebel, Felix Manz, Georg Blaurock, and Wilhelm Reublin, who, according to the Geschicht-Buch, "did not recognize infant baptism as a true baptism and demanded that one must and should be baptized in accord with Christian order and the institution of the Lord," i.e., be taught, and then baptized.

These Anabaptists found in Hubmaier their champion. On 17 January 1525, the well-known disputation was held in Zürich to settle the question, which, though its outcome was officially a victory for Zwingli's side, nevertheless won new adherents to the Anabaptist movement. Hubmaier now also in actual practice dropped infant baptism, baptizing only the children of such parents as were still weak in the faith and therefore desired baptism for their children. Anabaptists came to Waldshut and on 2 February 1525 Hubmaier published his Oeflentliche Erbietung, offering to prove in a public debate that infant baptism had no foundation in Scripture. But his request for a disputation was apparently not granted. Hubmaier's step had the support of a large part of the citizenry, but drew upon him the hostility of the Swiss reformers. He undertook further reforms in the order of divine service; after a period in which he conducted the Mass in German, he abolished it altogether and had the altars removed from the church, observed communion as practiced by the apostles, and finally, in accepting baptism by Wilhelm Reublin at Easter time, openly joined the Anabaptists.

The opposition of the Anabaptists had made of Zwingli an avowed champion of infant baptism. In reply to his book, Von der Taufe, der Wiedertaufe und Kindertaufe, Hubmaier wrote his booklet, Vom christlichen Tauf der Gläubigen, which is correctly regarded as the classic presentation of his teaching on baptism and as one of the best defenses of adult baptism ever written. It was directed against Zwingli, although it does not mention him by name, and made a profound impression on both friend and foe. Zwingli took up arms against it, and the council of Zürich thought it necessary to arrange another disputation, which was held on 6 November. Public opinion acclaimed Zwingli as the victor. Grebel, Manz, and Blaurock were summoned before the council and warned to desist from their teaching, and because they did not heed the warning they were taken to prison, so that if they persisted in separation, they should be most severely punished. Adult baptism and the postponement of infant baptism were forbidden. Zwingli's booklet against Hubmaier is dated 5 November, and Hubmaier's refutation 30 November, but the latter was not published until the following year at Nikolsburg in Moravia, after misfortune had descended upon Waldshut and its preachers.

Of equal significance with his religious activity was Hubmaier's political position. There is no doubt that he encouraged the city of Waldshut in its resistance against the Austrian government which led to armed intervention, and himself took part in the preparations for battle. Contemporaries and later writers have actually considered him the instigator of the Peasants' War. Thus the chronicler Letsch says, "and if one thinks this matter over properly, this Doctor Balthasar is a beginner and originator of the whole Peasants' War."

Wherever Hubmaier turned his steps later, this ill fame pursued him, and it did no good to resist it. In his booklet Eine kurze Entschuldigung, he said, "In being represented as an agitator, I fare as Christ did. He too had to be a revolutionary, and yet I testify with God and several thousand persons, that no preacher in all the regions where I have been has taken more pains and done more work by writing and preaching than I have that the government be obeyed; for it is of God. As concerns interest and tithes, I said that Christ also gave a third or a fifth. But the fact is: they tried to compel us to abandon the Word of God with force and contrary to law. This has been our only complaint." Likewise the people of Waldshut wanted to obey the house of Austria in all things, as their Erbietung says: "If there were a stone ten fathoms deep in the earth that was not truly Austrian," they would scratch it up with their nails and cast it into the Rhine.

Hubmaier expressed himself similarly in other writings. It has, of course, been demonstrated that he was not an instigator of the Peasants' War; nevertheless it is a fact that in Waldshut he was in close alliance with the peasants, supported them, and was aided by them. He assisted the citizens of Waldshut with counsel and helped them compose letters. He enlarged the peasants' Articles that came to his hands through the army, interpreted them, and told the people to accept them as Christian and reasonable. Much has been laid to his charge by his enemies, of which he was innocent. In Waldshut the point at issue in the entire conflict was not the removal or alleviation of feudal burdens, but, as Hubmaier expressly stated, the freedom of Protestant doctrine. If the people of Waldshut would only be granted religious liberty, they would be ready to fulfill all their obligations as Austrian subjects. But the government sought with a single blow to strike the peasants as well as the citizens of Waldshut who were fighting for the Gospel. It succeeded. First the peasants were defeated at Griessen, and then Waldshut was conquered.

With difficulty Hubmaier succeeded in escaping on 5 December 1525. In flight and with tattered garments he went to Zürich. The city refused to comply with the demand of the Austrian government to extradite him, kept him in light confinement, and arranged a disputation between him and Zwingli, which was held on 21 December 1525, but ended inconclusively. The city demanded that he recant, and he complied on 15 April - not without severe qualms of conscience; for while he was on the point of renouncing his teaching on baptism he prayed that God might again establish the two bonds of the Christian faith, baptism and communion; even if through fear of man and weakness of mind he was forced to yield these points by tyranny, torture, sword, fire, or water, he prayed the merciful Father in heaven to raise him up again and not permit him to part from this world without this faith.

In spite of his recantation his position in Zürich was precarious, for he was in danger of falling into the hands of imperial or Swiss enemies. He finally managed to leave Zürich secretly. He went to Konstanz and from there to Augsburg, where he associated with zealous Anabaptists, and in the summer of 1526 he turned his steps toward Austria, via Ingolstadt and Regensburg. His goal was Moravia, where several creeds lived side by side without molestation. In Augsburg, among others, he baptized Hans Denck.

Early in July 1526 Hubmaier arrived at Nikolsburg, which through his influence became for a time the center of the Anabaptist movement. Contemporary reports state that Hubmaier's presence there brought about an extraordinary influx of Anabaptists. About 12,000 are said to have gradually collected there and in the vicinity. The Geschichts-Bücher of the Hutterian Brethren also report, "In 1526 Balthasar Huebmör came to Nikolsburg in Moravia, began to teach and to preach, but the people accepted his teaching and in a short time many were baptized." This Moravian town became to the Anabaptists "what Emmaus was to the Lord, when He was asked to stay there." From all of South Germany they gathered and spread their teaching over all southern Moravia. Here they found the soil well prepared. The Protestants had formed a church here two years before, under the protection of the feudal lord, Leonhard von Liechtenstein; Hubmaier now made contacts with the preachers of this church, Hans Spitalmaier and Oswald Glait. The provost Martin Göschl of Kanitz also promoted his cause. Anabaptists of established reputation, including some who suffered a martyr's death for their faith, like Hans Hut, Leonhard Schiemer, and Hans Schlaffer, came to the community. The printer Simprecht Sorg of Zürich, called Froschauer, who had been staying in Styria for some time, was now called in by Leonhard von Liechtenstein, brought his entire print shop with him, and published all the works Hubmaier wrote after leaving Zürich. Most of them are dedicated to the heads of the Moravian nobility, with the intention of winning their favor to the Anabaptist cause.

Not all the Anabaptists remained true to Hubmaier. Among his opponents was Hans Hut, an apostle of the Anabaptists in Upper and Lower Austria, with whom many of Hubmaier's former friends sided, because in their opinion Hubmaier's program was too moderate. Hut had even before the Peasants' War preached the coming of the last day; he adhered to these chiliastic views, and opposed Hubmaier especially on the questions "of the sword," and whether war taxes should be paid. Hubmaier tried to remove the tension by means of a disputation, which was held at Bergen, a village near Nikolsburg. The discussion centered on community of goods and war taxes. The Anabaptists were faced by a dilemma by the demand for war taxes, for on the one hand they were compelled by law to pay them, and on the other hand their religious principles forbade warfare or the payment of taxes to wage war. The disputation did not achieve the desired result of unity. A second disputation ended similarly. Hans Hut was "held in the castle against his will by the lord of Liechtenstein, because he would or could not agree with him to bear the sword"; he was, however, released at night by a friend. Hut's opposition caused Hubmaier to speak of it openly once more in the "Spital," and in his final book he again discussed this controversy: he rejected all violence, to which Hut was evidently inclined, and told him and others this to their faces. From the cross-examination of an attendant at the Nikolsburg disputation it is learned that other subjects were also discussed there: baptism, communion, the Last Judgment, the end of the world, the new kingdom, and the coming of Christ. The Nikolsburg disputation attracted attention far beyond the borders of Moravia, as can be seen in the "Articles from Moravia," which claim to be the teaching of the Anabaptists, but which mingle much that is false with the truth.

The conflict between Hut and Hubmaier resulted in Hubmaier's publishing his teachings in a series of pamphlets; but, assured of the powerful support of the nobility he was also able to refute earlier rumors spread by his opponents. Thus in the short period of one year he published no fewer than 18 works, some of i which he had written before coming to Nikolsburg. The first, probably finished at the end of November 1525 and published in July 1526, was his Gespräch auf Meister Ulrich Zwinglis Taufbüchlein von dem Kindertauf. When he wrote it he evidently did not yet know of Zwingli's sharp reply to his book Vom christlichen Tauf (see above), since he did not mention it. He complained about the severe suffering he endured in Zürich, where he "wished to present the proof in the divine Word that infant baptism is a work without any foundation in the divine Word." He complained further of Zwingli's severe attitude toward the Anabaptists, who, he (Zwingli) preached, should be beheaded. At Zwingli's instigation about 20 Anabaptists had been put into prison, there to die. At the same time an edict was issued which threatened all Anabaptists with drowning. In this manner he overcame the Anabaptists, but not a Scripture did he produce against them; instead, as he admitted in his booklet Von den aufrührigen Geistern, those who baptized children had no foundation for it in Scripture. "In my teaching," continues Hubmaier, "the Holy Scripture shall be the judge, in temporal affairs the government, to whom God has given the sword, to protect the godly and to punish the wicked." He did not want to take revenge on Zwingli, but only contribute to the re-establishment of the church. Four other booklets which were already finished, were to deal with these subjects: (1) a catechism or Lehrtafel, what a man should know before he is baptized with water; (2) what Christian water baptism is; (3) a Christian church order; and (4) a reply to the mocking speech of some preachers in Basel. Hubmaier had great expectations from this polemic against Zwingli: in six years no article had been published which offered clearer proof that infant baptism should not be permitted.

The booklet itself consists of five parts, of which the third is the most important, maintaining that one can become a disciple of Christ only by teaching and faith. When Jesus commanded that all believers should be baptized, all those were excluded who had not been instructed in the faith. To Zwingli's "most powerful argument," that the baptism of children (like circumcision with the Jews) is "an anhebend sign" whereby we obligate ourselves, Hubmaier replies: The child weeping in its cradle knows nothing of a sign, or a duty, or a baptism. In summary, Hubmaier teaches: (1) no element, only faith, cleanses the soul; (2) baptism cannot wash away sins; (3) it is therefore only a testimony of the inner faith and a sign of the obligation of a new life; (4) whether infants are God's children may be left to God; (5) Noah's ark rather than circumcision is a figure of baptism; (6) only adult baptism is founded upon Scripture. Infant baptism is not of God. Hubmaier asked where there is mention in the Bible of a godfather.

The four booklets mentioned are directly connected with this polemic against Zwingli. But first Hubmaier published a booklet dedicated to the provost Göschl, Der uralten und gar neuen Lehrer Urteil, dass man die Kinder nicht taufen solle, bis sie im Glauben unterrichtet sind. It is a collection of quotations which prove that in all periods outstanding men of the church have preferred adult baptism to infant baptism. Since every Christian must be instructed before he is baptized, Hubmaier wrote Eine christliche Lehrtafel, die ein jeder Mensch, bevor er im Wasser getauft wird, wissen soll. The foreword is dated 10 December 1526. This Lehrtafel was intended to in general remove ignorance, namely, among the clergy. The depth of this ignorance he reported from his own experience: "With my own blush of shame I testify and say it openly, that I became a Doctor in the Holy Scriptures without understanding this Christian article which is contained in this booklet, yea, without having read the Gospels or the Pauline epistles to the end. Instead of living waters, I was held to cisterns of muddy water, poisoned by human feet." In the form of a dialogue between Leonhard and Hans (the Christian names of his sponsors in the house of Liechtenstein) he discussed the articles of the Christian faith.

The next book has the title Von der brüderlichen Strafe; it may be the same book that he had earlier called Eine Ordnung christlichenkirche, and brought to Nikolsburg completed. It deals with the need for church discipline, and gives instructions for brotherly admonition. It was printed with Von christlichen Bann early in 1527. It was followed by Grund und Ursach, dass ein jeglicher Mensch, der in seiner Kindheit getauft ist, schuldig sei, sich recht nach der Ordnung Christi taufen zu lassen, ob er schon 100 Jahre alt ware. It was dedicated to Johann von Pernstein auf Helfenstein, the governor of Moravia. In it Hubmaier presented 13 reasons that obligate men to be baptized according to Christ's order, even if they had already been baptized in childhood. This book is a supplement to his Taufbüchlein, and was in all likelihood finished before 1526. It was not published until the following year.

The last book, the outline of which was drawn up in Switzerland, is the reply to the well-known book by Oecolampadius, and has the title, Von dens Kindertauf; Oecolampadius usw., Ein Gespräch der Prädikanten zu Basel und Balthasaren Huebmörs von dem Kindertauf. It is a refutation of the book by Oecolampadius, Ein Gespräch etlicher Pradikanten zu Basel, gehalten mit etlichen Bekennern des Wiedertaufs, which was published at Basel in 1525. Hubmaier defended his teaching that Christ ordained baptism for believers, and not for infants. He replied to Oecolampadius's objection that councils, St. Augustine, and the tradition of the church confirm infant baptism, with the argument that faith must be founded not on councils, nor on tradition, but on the Holy Scriptures. "If you can show me a single instance of infant baptism in the Bible, I am defeated. Anabaptist doctrine is therefore not new, but derives from Christ."

One of the books which Hubmaier brought to Moravia more or less completed has no polemic character. It is Zwölf Artikel des christlichen Glaubens zu Zürich ins Wasserthurm betweis gestellt, Hubmaier's confession of faith. Here too his teaching on baptism and communion formed the basis for his arguments. He fervently prayed that God might re-establish the two bonds with which He has girt the church, viz., baptism and communion. The book was written 15 April 1526, and printed in 1527.

Written after this book, but published before it, was his Entschuldigung an alle christgläubigen Menschen, dass sie sich an den erdichteten Unwahrheiten, so ihm seine Missgönner zulegen, nicht ärgern, printed in 1526. It is a defense against the many untruthful charges made against him in four years. To this point he had patiently borne them, and would continue to bear them, but because so many spirits were offended by them he found it necessary to defend his innocence. He was accused of dishonoring the mother of God, of rejecting the saints, of discarding prayer and the confessional, fasting, the Church Fathers, the councils, etc., in short, of being the arch-heretic. He replied that his teachings were not innovations; he preached Christ and the Gospel, considered Mary both before and after the birth a pure virgin, honored the saints as God's tools, taught prayer without ceasing, fasted daily; confession must be made hourly; i.e., mourn one's sins; a rattling confession would of course not do; the teachings of the Church Fathers, councils, etc., he tested by the touchstone of the Holy Scriptures. He did not regard monks and nuns, taught the true baptism of Christ, which is ruined by infant baptism; the latter is a misuse of the name of God and a disparagement of Christ; of the Mass the Scriptures contain nothing; the "Pfaffenmesse" is of no more avail than the "Frankfurter Messe"; for at both one can buy and sell every day. If he was called an insurgent and a misleader of the people who preached against the government, he could testify with God and a thousand witnesses that he held the people to obedience toward the government; for it is of God. Without murmuring one must give the taxes, tithes, and tributes and pay it honor and reverence. He then enumerated the persecutions to which he was subjected by the Austrian government, and the slanders broadcast during his stay in Regensburg and Ingolstadt. He protested against the charge that he was a heretic, lamented Zwingli's tyranny without mentioning him by name. This book doubtless originated during his residence in Nikolsburg; it must have been of importance to him to prove that the slanders spread abroad were unfounded.

A considerable number of the works of Hubmaier that follow have didactic contents. His Kurzes Vaterunser (Nikolsburg, 1526) is a devotional booklet. In his Ein ein einfältiger Unterricht auf die Worte, das ist der Leib mein im Nachtmahl Christi (Nikolsburg, 1526) he shows "that the breaking, distribution, and eating of the bread is not the breaking, distribution, and eating of the body of Christ, who is in heaven seated at the Father's right hand, but that it is a memorial of His body, an eating in the faith that He suffered for us. And as the bread is 'the body' of Christ in memorial, so is also the blood of Christ a memorial." The book is dedicated to Leonhard von Liechtenstein, to whom a few words of appreciation are addressed, and Nikolsburg is compared with the Biblical Emmaus. In it Hubmaier opposed Luther's concept of communion no less than Zwingli's.

The next book, titled Eine Form zu taufen in Wasser die im Glauben Unterrichteten (Nikolsburg, 1527) and dedicated to "Johann Dubschansky von Zedenin und auf Habrowan," contains the baptismal ceremonies "as we apply them at Nikolsburg and elsewhere." Whoever wished to be baptized must notify the bishop, so that the latter might examine him to see whether he had been adequately instructed in the articles of the law, the Gospel, and the doctrine, whether he could pray, and with understanding state the doctrines of the Christian faith. If this was the case, the bishop presented him to the congregation, and urged all the believers to ask God to grant him grace. Then followed the formula of the prayer and the baptismal vow, then the baptism, laying on of hands, and the reception of the candidate into the congregation.

A similar purpose was to be served by Eine Form des Nachtmahls Christi (1527). It is dedicated to Lord Burian of Cornitz, a Moravian nobleman who was zealously devoted to the cause of the Reformation, and was sent to him by the (Bohemian) Brother Johann Zeysinger. Hubmaier referred to his booklet, Ein einfältiger Unterricht, as a dogmatic presentation of communion, and here presented "in what form communion is held in Nikolsburg." The church was to be called to a fitting place at a suitable time, the table set with ordinary bread and wine, which requires no silver goblets. The priest reminded the audience of their sins, explained the Scriptures that deal with reformation of life and the new birth, asked them individually whether a proper understanding was still lacking, and instructed them, then took the passage on communion and closed, "Let him who would eat of this bread arise and perform his duty of love with heart and mouth, declare his intention to love God and his neighbor, obey the government, submit to brotherly reproof, and desire to eat at the Lord's table." With a prayer of praise and thanks the communion was then taken. Then the congregation again assembled for the closing prayer and the repeated admonition to live a Christian life.

The booklet Von der brüderlichen Straf (Nikolsburg, 1527), which is probably identical with the Ordnung der christlichen Kirche, and was thus written in Waldshut, proceeds from the idea that "all labor and toil is in vain, baptism and communion futile, if church discipline is not practiced in the church as ordained by Christ; this has been clearly seen in the past few years, when the people, without changing their conduct in life, have learned nothing more than two things. One group says that faith alone saves; the other, that we of ourselves can do nothing good. Both statements are true, but under cover of these truths malice, faithlessness, and unrighteousness have become prevalent, and brotherly love has cooled off more than in 1000 years before. There is only one remedy: Openly committed sins must be punished as a deterrent to others; for such sins eat like a cancer if they are not rooted out; for what one does, the other considers permissible. Secret sins must be punished in secret, as the Lord commands; first before one person, then before two or three witnesses, and finally before the entire congregation. If the question is raised where anyone gets the authority to punish his brother, the answer is, from the baptismal vow, in which each obligates himself to live according to Christ's ordinances. When the brother has been punished in accord with Christ's regulation, and if he still will not forsake sin, then according to the command of Christ he must be excluded from fellowship and banned."

The booklet Vom christlichen Bann (Nikolsburg, 1527) appropriately continues the subject of punishment. It is therefore, says Hubmaier, necessary to know what the ban is, the source of the authority of the church, how banning should be carried out, and what to do with the excommunicated member. The ban is the public excommunication of the obstinate sinner from the Christian brotherhood, to the end that he will not give offense in the church, but will rather confess his sin and reform. Christ employed the ban both in word and deed and left it to the church, which then excludes the wicked, unfaithful, and disobedient from the Christian brotherhood. Concerning the form of the ban Hubmaier says that the brother to be expelled has broken the vow he made at his baptism and communion. Therefore the church is excommunicating him. With the expelled member no fellowship may be had henceforth; yet he shall not be treated as an enemy, beaten or killed, but avoided, for the punishment is not given in hatred, but in Christian love for the benefit of the sinner. Hubmaier does not neglect to point out the flagrant abuses that the clergy have practiced with their anathemas, usually pronounced with unchristian motives. If one did not immediately believe what church law commanded, he was from that hour placed under the false ban instead of the Christian, and the secular arm had to be his constable. The man, continues Hubmaier, is released from the ban when he confesses his sin and repents. Naturally if the great lords, nations, and cities refused to accept this regulation of brotherly punishment and of the Christian ban, then it is difficult to set up a Christian regime there.

With nearly the same words as in the book on brotherly punishment Hubmaier in his book Von der Freiheit des Willens (Nikolsburg, 1527), dedicated to Georg, Margrave of Brandenburg, says that the people have learned only these two things from the preaching of the Gospel: faith saves, and we have no free will. These statements are only half-truths, from which only a half judgment can be formed. Such half-truths do more damage than complete lies, for they are rated by their appearance of whole truths. People then push their guilt upon God as Adam did upon Eve, and she upon the serpent. To root out such blasphemy is the object of this book; this concept includes how and what man is and can do within and without the grace of God. Man consists of three parts, body, soul, and spirit. Therefore three wills must be recognized, that of the flesh, that of the soul, and that of the spirit. Before the sin of Adam all three parts of man were free and good. After his fall he lost this freedom: as a vassal who is untrue to his lord loses his fief not only for himself, but also for his heirs, so the flesh has lost its freedom through Adam's fall and must return to the earth whence it came. The spirit has remained good, but as a prisoner of the flesh had to eat too; the soul, becoming ill through Adam's disobedience, has lost the knowledge of good and evil and is powerless to carry out the good. Since the fall of man the flesh is useless, the spirit willing to do good; the soul stands between in concern; but, healed by Christ, it has again acquired its lost freedom and can willingly obey the spirit and will the good. Thus it depends only on the soul. According to its decision man is saved or damned. Through Adam's fall man received two wounds, an inner one, which is the inability to recognize good and evil; and an outer one, in doing and carrying out. The former is healed through the law, which teaches him to distinguish between good and evil; the other is healed through the Gospel. Thus no one can use lack of liberty as an excuse; for what Adam lost, Christ brought back.

Das andere Büchlein von der Freiwilligkeit des Menschen (Nikolsburg, 1527) was finished on 20 May 1527, and dedicated to Duke Friedrich von Liegnitz und Brieg. It shows, as is said in the title, that God through His Word gives men the power to become His children and commits to them the decision to will and to do good. It contains the passages of Scripture that show that before the fall man had the grace to keep God's commands and be saved; then those passages that show that man has regained the freedom lost through Adam. In the second part follow the conclusions, which show the purpose of the book most clearly. Some of these are as follows: He who knows what the new birth is will not deny, the freedom of the human will. He who says that the flesh does not need to will contrary to its natural will or perform the will of. the soul that has been awakened by God, gropes along a wall in midday. That lord is foolish who sets a goal for his people and says, "Go on, run that you may win," when he knows that they are in chains and are incapable of running. All things happen in accord with God's will: the good in the power of His word, the evil to punishment. God wills that men should do good; He also wills that he who will not do good be the master of his own works and do evil, that the forsaking of the good may be punished in him. We do not know whom God has elected and which of the two He will give, blessedness or damnation. In the third part he discusses the objections that have been made. He explains 16 situations. Thus if one says to him: God has mercy on whom He will and hardens whom He will, he replies: There is an absolute will of God which is subject to no rule, and a revealed will, which wants all men to be saved. Of course, God does not have two wills; this is a figure of speech so that we may understand.

Already in his Kurze Entschuldigung Hubmaier had expressed himself on the attitude of men to their authorized government and defended himself against the charge that he was a rabble-rouser and heretic. He develops this further in his Vom Schwert (1527), which he dedicated to Lord Arkleb von Boskowitz und Tschernahora auf Trebitz, chief Landeskämmerer of Moravia. He wished to present in it what had always been his conception of government. More earnestly than any other preacher he observed the Scriptures on government, but he also pointed out to the tyrants their vices. Hence the envy, hate, and hostility towards him. Hubmaier first treats those passages with which his enemies attack him and then cites those which form the basis of his attitude. His opponents, for example, point out the passage, my kingdom is not of this world. If the kingdom of Christ is not of this world, then he would not be permitted to bear the sword. But the passage merely states that our kingdom should not be of this world. But alas, it is of this world, as we ourselves pray in the Lord's Prayer: Thy kingdom come. Or the opponents quote: Put up thy sword. But here Christ was merely saying that those should not bear the sword who are not entitled to do so; else they will perish by the sword. In the same manner all the passages are explained. For the affirmation of government among Christians Hubmaier cites the verse: Let every soul be subject to the higher powers. For there is no power but of God. This passage alone is sufficient to establish the government against all the gates of hell. Subjects should, of course, examine the spirit of their governments, whether they rule out of pride, envy, hatred, or self-seeking rather than for the common welfare and peace. This is not bearing the sword against the government. But when the government punishes the evildoers to create peace for the good, then help, then advise, then support, as often as it is asked of you. Only when the government is childish or foolish or cannot reign wisely, then if one can legally escape it is good to do so, for God has often punished an entire country on account of a bad government. .But if it cannot be done without insurrection, then endure it. No doubt this booklet was intended also to make good the impression that the Nikolsburg disputation must have made on the ruling classes.

Hubmaier's Arrest, Imprisonment, and Martyrdom

While Hubmaier was increasingly promoting his teaching, the Anabaptist movement with its elemental force spread throughout the Austrian hereditary lands. From all sides reports reached the government on the success of the Anabaptist movement and advice for its suppression. Ferdinand I had after the death of King Louis of Hungary and Bohemia in the battle of Mohács acquired these lands and it was doubtful that he would deal as tolerantly in Moravia as his predecessors had done. He was particularly disquieted by the reports he received from the Austrian authorities. He did not fail to issue edicts for the suppression of the Anabaptists. On 12 August 1527 he sent a letter to the citizens of Freistadt in Upper Austria with the command to seize Hans Hut, Hubmaier's former associate. But more important to the government than Hut's capture was the capture of Hubmaier, its old opponent from the time of Waldshut, to whom, according to a contemporary eyewitness, masses of people were streaming from the adjacent regions. Hubmaier had no intimation of the danger hovering over him when he signed the foreword of his book on the sword. Four weeks later he found himself imprisoned in Vienna. The details of his capture are not known. The Geschichts-Bücher only record that Ferdinand I had cited Hans and Leonhard von Liechtenstein to Vienna together with their chaplains. "From that hour Balthasar Huebmör with his wife was seized and sent to the Kreuzenstein castle." Hubmaier's extradition was not so much a consequence of his religious work as of his political activity in Waldshut; for the persecution of Anabaptists was not permitted in Moravia until after the edict of the diet in March 1528. Some manuscripts of the chronicles state that Hubmaier was forged to a wagon when he was seized in Nikolsburg, and was thus taken to Vienna. That in the Hubmaier affair the primary issue was his political activity in Waldshut is seen in the command Ferdinand issued to his government in Ensisheim to conduct a careful investigation of Hubmaier's actions in Waldshut, where he caused insurrection and revolt among the common people. His teachings occupy a subordinate place; certain individuals in Waldshut are to be questioned about them. The government in Ensisheim as well as that in Innsbruck complied with the order. Two "witnesses" in Hubmaier's own hand are sent in, one of which had much to say "against Luther"; the second indicated "that his spirit had tended to awaken insurrection against the government"; those in Waldshut had been the first and the last to persist in it and conduct themselves according to the Doctor's teaching.

Kreuzenstein is a castle in Lower Austria, now rebuilt from its ruins, three quarters of an hour north of Korneuburg. When Hubmaier was taken there is not certain. It is only known that he lay in prison in Vienna several weeks. But at the turn of the year he was in Kreuzenstein; for from that place on 3 January 1528 he sent his booklet, Eine Rechenschaft seines Glaubens, to Ferdinand I. Kreuzenstein was at that time a possession of Niklas, Duke of Salm, but was used as a state prison, and was in a bad state of repair.

Stephan Sprugel, the contemporary and eyewitness of Hubmaier's execution, reports that Hubmaier enjoyed numerous visits by learned men of good repute, who, with good intentions and sympathy urged him to renounce his errors. Hubmaier himself bemoaned his strict confinement. Illness and other difficulties had come upon him, and he suffered from want of books. The prospects for release were not favorable, even if he would recant, because of his activity in Waldshut.

In his need Hubmaier cast his longing glances upon Johannes Faber, his erstwhile fellow student and friend, but now his opponent, and addressed a petition to King Ferdinand to grant him a conference with Faber. This was granted. Faber described the course of his conversation in his booklet, Adversus D. Balthasarum Pacimontanum . . . orthodoxae fidei catholicae defensio. He had gladly acceded to Hubmaier's wish, for he had known him for years and had cultivated friendly intercourse with him while he carried on his studies with him, being still of irreproachable character. Faber was accompanied to Kreuzenstein by Markus Beckh of Leopoldsdorf and Ambrosius Salzer, the rector of the University of Vienna.

During the conversation Hubmaier said: What I have hitherto taught and written, I have not taught for the purpose of securing privileges for myself, but because, as I think, God's Spirit seized me. The colloquium, which took place in late 1527 lasted several days—on the first day until after midnight. Topics under discussion were the exposition and correct understanding of the Bible tradition and infant baptism; on the second day the altar sacrament, sacrifice of Mass, intercession of saints, and purgatory; on the third day faith and good works, Christian liberty, freedom of the will, the worship of Mary, the last things, penitence and confession, the power of the keys, Lutheran and Zwinglian doctrine, and the Councils.

At the close of the conversation Hubmaier declared his intention of presenting his confession of faith to the king. He carried out this intention without delay, and wrote the Rechenschaft seines Glaubens. He requested that the king most graciously listen to it and grant him grace and mercy. The Rechenschaft contains 27 articles, most of which are so worded that any Christian could subscribe to them; and in the two most important points, not so worded, he is willing to submit to the decision of a council, but in the meantime "stand still" on these points.

Hubmaier was mistaken in supposing that his defense would ease his situation. Precisely on the two points mentioned the authorities had looked for unconditional yielding, and said that he had expressed only half an opinion and had not presented a complete revocation. During the last days of February 1528 he wrote a second booklet, which is unfortunately no longer in existence, in which he discussed both points again. But since this document did not contain the required recantation either, Hubmaier was led back to Vienna, and before the heresy court tried on the rack; when this did not produce a recantation he was sentenced to die at the stake. His wife encouraged him; she was, as Sprugel comments, even firmer in her faith than her husband. When Hubmaier was taken to the site of execution, on 10 March 1528, he spoke words of comfort to himself by reciting Bible verses. When he arrived at the scaffold, accompanied by a great crowd of people and followed by an armed company, he raised his voice and cried out in the Swiss dialect, "O my gracious God, grant me grace in my great suffering!" Turning to the people he asked pardon if he had offended anyone, and pardoned his enemies. When the wood was already in flames, he cried out, "O my heavenly Father! O my gracious God!" and when his hair and beard burned, "O Jesus!" Choked by the smoke, he died. To the spectator it appeared that he felt more joy than pain. As the Geschichts-Bücher relates, he sealed his faith with his blood like a knight. His wife, the Waldshut citizen's daughter, did likewise. A few days later she was thrown from the large bridge over the Danube with a stone tied about her neck and drowned.

The men who had been seized with him recanted, except two who likewise died in flames on 24 March. On the pyre they sang, "Come, Holy Spirit."

Hubmaier's death aroused consternation not only in Lower Austria and Moravia, but far beyond their borders. Because it was said in many places that he had been unjustly treated and was a martyr before God, and like John Hus innocently burned, Faber had a pamphlet printed in 1528 with the title, Ursach, warumb der Widertauffer Patron und erster Anfänger Doctor Balthasar Hubmayr zu Wien auf den zehnten Martii anno 1528 verbrennet sei.

Hubmaier's large literary output has been listed above. Two of his hymns were known by the Hutterian Brethren, but only one has been preserved, which is based on his constant motto, "God's truth will stand eternally," and begins, "Freut euch, freut euch in dieser Zeit." If the Geschichts-Bücher do not record much about Hubmaier, it must be remembered that he was not only not a member of the Hutterian Brethren, but was in opposition to a central doctrine of the group, namely, nonresistance.

The question of the influence of Hubmaier on Peter Riedemann (and thereby the Hutterian Brethren) has been thoroughly examined by Franz Heimann ("The Hutterite Doctrines of Church and Common Life, A Study of Peter Riedemann's Confession of Faith of 1540," MQR 36, 1952, particularly pp. 142-145, and 160). He says:

"The remark of Johann Loserth [Communismus, 226], that Riedemann's Rechenschaft closely follows the writings of Hubmaier, is by and large correct as far as the teachings of baptism, Lord's Supper, and ban are concerned, even though in these points there is no literal identity. Hubmaier's influence upon the Anabaptists with regard to baptism and Lord's Supper is clearly recognized at one place of the Hutterite Chronicle. At the occasion of Hubmaier's martyrdom and death, the Chronicle writes:

"Two hymns are still in our brotherhood which this Balthasar Hubmaier composed. There are also other writings by him from which one learns how he had so forcefully argued the right baptism, and how infant baptism is altogether wrong, all this proved from the Holy Scriptures. Likewise he brought to light the truth of the Lord's Supper, and refuted the idolatrous sacrament and the great error and seduction by it' [Zieglschmid, Chronik, 52].

"There exists a common Anabaptist understanding both in Riedemann and Hubmaier as far as they deal with the fallen state of man, the inner rebirth in faith, and the testimony of this faith in confession and life, presupposing the freedom of man to obey God's commandments. Beyond that also the teaching concerning the right sequence of preaching the Word, hearing, change of life, and baptism, seems to be derived from Hubmaier. In addition, Riedemann seems to have borrowed from him almost in its entirety the polemic against infant baptism (70-77) with all its numerous arguments and reasons, in which polemic Hubmaier nearly exhausted his theological capacity. There is also a fairly complete agreement of the Rechenschaft with Hubmaier's teachings concerning the 'Fellowship of the Lord's Table,' whose inner communion must already be present prior to the breaking of the bread. Likewise we find already in Hubmaier the teaching of the Christian brotherhood or church (Gemeinschaft), which exercises inner discipline by brotherly punishment and the ban. It seems fairly apparent that Riedemann knew and used Hubmaier's tracts and books such as: Eine christliche Lehrtafel; Ein einfältiger Unterricht auf die Worte: das ist mein Leib, in dem Nachtmahl Christi; Eine Form zu taufen in Wasser; Eine Form des Nachtmahls Christi; Von der brüderlichen Strafe; and Vom christlichen Bann. Riedemann used these books primarily for his chapters 'How One Should Baptize,' 'The Misuse of the Lord's Supper,' 'Concerning the Supper of Christ,' 'Concerning Exclusion,' and 'Concerning Readmission.'

"The closest contact between Riedemann and Hubmaier is to be found in the concern for the awakening of the Christian individual and for the brotherhood which in Anabaptist thought coincides with the church in general. In the center of Hubmaier's religious thinking stands the inwardly united 'Fellowship of the Lord's Table,' which breaks the bread as a sign of love and readiness for sacrifice (Hubmaier, Eine Form des Nachtmahles Christi, Nikolsburg, 1527). The religious ideal of Riedemann, on the other hand, is more the spiritual fellowship of the body of Christ, or the Holy Church without spot or wrinkle, into which the individual who is longing for Christian fellowship is accepted by the right sequence of hearing the Word, believing, rebirth, and baptism. By this the church becomes a true `fellowship of committed disciples.' In Riedemann's vision it is in the idea of discipleship of Christ that the unity of the Spirit takes on flesh and blood and becomes a true church.

"Concerning 'brotherly punishment' and 'Christian ban,' Hubmaier sees in them the means to secure the purity of the 'Fellowship of the Lord's Table.' Riedemann would agree, but he sees the fellowship 'of the children of God' much more concrete and wide, and he interprets the ban much more radically in view of the purity and sacredness of his community. In the Rechenschaft the doctrine of the fellowship of the Lord's Table is closely connected with the doctrine of separation from the world, in complete agreement with the Schleitheim Articles. The latter require expressly in Article II that the ban be employed prior to the breaking of the bread, `so that we may break and eat one bread with one mind and in one love, and may drink of one cup.' Likewise in Article IV the complete separation of the children of God from the wickedness of this world is required.

"The idea of an absolute contrast of the pure church of the children of God to the impure 'world' is basic for the Hutterite brotherhood. From it all further characteristic traits derive, and upon these, it should be emphasized here, Hubmaier's ideas had no influence whatsoever. It was, we should remember, Jakob Hutter who took the step of organizing the final brotherhood and of establishing the way of life in complete communion of goods as the expression of brotherly love and self-surrender (143-45)."

Heimann concludes: "In general it can be said that the teachings of Hubmaier concerning baptism and the Lord's Supper are reflected in the Rechenschaft of Riedemann; in fact, they represent teachings espoused by practically all evangelical Anabaptists. Beyond that, however, Hubmaier had no tangible influence upon Riedemann's thinking. With the arrival of Jakob Hutter in Moravia, late in 1529, the time of compromise had come to an end, and the spirit of strict and committed discipleship, the 'narrow path,' became dominant."

A complete translation into English of all Hubmaier's extant writings has been made by William O. Lewis and deposited in the William Jewell College Library at Liberty, Missouri, USA). A microfilm copy of this manuscript is found in the libraries of Bethel College and Goshen College.

The [[Amsterdam Mennonite Library (Bibliotheek en Archief van de Vereenigde Doopsgezinde Gemeente te Amsterdam)|Amsterdam Mennonite Library]] has the following books by Hubmaier:

Prugner, N. and B. Fridberger. Acht unnd dreyssig schluszrede so betreffende ein gantz Christlich leben war an es gelegen ist. no publisher indicated, 1524.

Fridberger, B. Achtzehen schluszrede so betreffende ein gantz Christlich leben. No publisher indicated, 1524.

Schluszreden die Balthazar Fridberger dem I. Eckio die meysterlich zu examinieren fütbotten hat. No publisher indicated: Not dated.

Frydberger,B. Ain Summe ems gantzen Christlichen lebens. No publisher indicated 1525.

and written copies made in the 19th century of:

Huebmör, B. Von Ketzern und iren Verbrennen. 1524; Ein gesprech . . . auf Mayster Ulrichs Zwinglens Tauffbüchlen. 1526; Der Uralten und gar neuen Leerern Urtail. 1526; Zwölf Artickel Christlichen Glaubens zu Zürich im Wasserturm gestellt. 1527. -- Johann Loserth

1990 Update

Balthasar Hubmaier was an Anabaptist theologian and martyr. Educated at the universities of Freiburg (im Breisgau) and Ingolstadt. In the latter university he was both the prorector and lecturer in theology before becoming cathedral preacher at Regensburg. In 1521, Hubmaier became pastor at Waldshut. While here he began to embrace certain Reformation concepts. By the October Disputation in Zürich (1523), after a brief second stay at Regensburg, he openly championed the Swiss Reformation. Upon his return to Waldshut he began to reform the faith and order of his church and those of his fellow priests. His reformatory efforts were accompanied by a vigorous writing campaign in which he set forth a form of Reformation teaching that was neither Lutheran nor Zwinglian but had an affinity with the emerging Anabaptism of Zürich. By Easter, 1525, Hubmaier was baptized by Wilhelm Reublin along with 60 of his parishioners and he, in turn baptized some 300 others. The Anabaptist movement in Waldshut was short-lived since a threatened invasion by Austria drove Hubmaier and his wife from the city. After imprisonment and torture in Zürich, he managed to escape, a chastened and subdued man. Hubmaier next became the leading pastor in Nikolsburg, Moravia, in 1526 where he won local preachers for Anabaptism and the Lichtenstein barons, as well. It was here that Anabaptism enjoyed in greatest numerical success. After 16 or 17 months, Hubmaier and his wife (Elizabeth Hugeline) were arrested by King Ferdinand of Austria, who had recently acquired jurisdiction of Moravia. After a time of imprisonment in Vienna and the Kreuzenstein Castle, where he was tortured, Hubmaier was taken to Vienna and burned to death on 10 March 1528. His wife was drowned in the Danube three days later.

Controversial in life, Hubmaier was no less so in death. Although he was not a thorough-going pacifist, neither was he the militant advocate of war he has at times been represented. He did hold the possibility of a Christian magistrate and argued further that a Christian would make a better magistrate than a non-Christian. In all other major doctrines he was in step with the majority of Anabaptists. In fact, he was the most eloquent spokesman and profound theologian of 16th-century Anabaptism. His writings on religious freedom, baptism, and freedom of the will became foundational. He can be considered the theologian of the "new birth" for he was the first to articulate clearly the concept that became basic in Anabaptist and Mennonite self-understanding and an essential ingredient in evangelical soteriology. Hubmaier's lasting significance is evident more in his writings than in personal influence. Even the Hutterites, whose leader he had opposed in Nikolsburg, were greatly indebted to him for much of their faith and practice. His published works in German and in English still stimulate and challenge those who like Hubmaier hold to believers' baptism. -- William R. Estep, Jr.

Bibliography

A book also very likely written by Hubmaier. " Ein warhafitig Entschuldigung und Klag gemeiner Stadt Waldshut von Schultheis und Rat aldo an alle christgläubig Menschen ausgangen anno 1525." printed by J. Loserth in "Die Stadt Waldshut und die vorderösterreichische Regicrung in den Jahren 1523-1526." Archiv für österreichische Geschichte 77: 1-149.

Beck, Josef. Die Geschichts-Bücher der Wiedertäufer in OesterreichUngarn. Vienna, 1883; reprinted Nieuwkoop: De Graaf, 1967.

Bergsten, Torsten. Balthasar Hubmaier: Seine Stellung zu Reformation und Taufertum, 1521-1518. Kassel, 1961. [Abridged English translation: Valley Forge: Judson Press, 1978].

Estep, Jr., W. R. "The Anabaptist View of Salvation." Southwestern Journal of Theology 20, no. 2. (1978): 32-49.

Estep, Jr., W. R. "Balthasar Hubmaier: Martyr without Honor."Baptist History and Heritage, 13, no. 2 (1978): 510, 27.

Estep, Jr., W. R. "Von Ketzern und iren Verbrennern: A Sixteenth Century Tract on Religious Liberty." Mennonite Quarterly Review, 43 (1969): 271-282.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: v. II, 353-63.

Hosek, F. Balthasar Hubmaier a pocatkov en ovo Krestenstva na Morave. Brno, 1893.

Klaassen, Walter. "Speaking in Simplieity: Balthasar Hubmaier." Mennonite Quarterly Review 40. (1966): 139-147. [examines Hubmaier's hermeneutics].

Die Lieder der Hutterischen Brüder. Scottdale, 1914.

Mau, W. "B. Hubmaier." Abhandlungen zur mittleren und neueren Geschichte. No. 40. Berlin and Leipzig, 1912.

Pipkin, H. Wayne and John H. Yoder. Balthasar Hubmaier: Theologian of the Anabaptists, Classics of the Radical Reformation, vol. 5. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1989.

Rempel, John D. "Christology and Lord's Supper in Anabaptism: A Study in the Theology of Balthasar Hubmaier, Pilgram Marpeek, and Dirk Philips." ThD discourse, St. Michael's College, Toronto School of Theology, 1986.

Sachsse, C. "D. Balthasar Hubmaier als Theologe." Berlin, 1914.

Schreiber, H. "B.. Hubmaier." Taschenbuch für Geschichte und Altertum in Süddeutschland. Freiburg,1839.

Sprugel, S. "Bericht Ober Hubmaiers Tod." Acta facultatis artium IV, 149b. University archives in Vienna. Reprinted in Mitterer, Compectus hist. Univ. Viennensis. 1724.

Stayer, James M. Anabaptists and the Sword. Lawrence, KS: Coronado Press, 1972; revised ed. 1976: esp. 104-7. 141-45.

Steinmetz, David C. "Scholasticism and Radical Reform: Nominalist Motifs in the Theology of Balthasar Hubmaier." Mennonite Quarterly Review, 45 (1971): 123-44.

Stern, A. "Ueber die 12 Artikel von 1525 u. ihre Verfasser." Historische Zeitschrift XCI.

Vedder, H. C. Balthasar Hubmaier, the Leader of the Anabaptists. New York and London, 1905. In Heroes of the Reformation, contains a portrait of Hubmaier, which is probably not contemporary.

Westin, Gunnar and Torsten Bergsten. eds., Balthasar Hubmaier Schriften, vol. 29 in Quellen zur Geschichte der Muter IX. Karlsruhe, 1962: critical edition.

Wiswedel, W. Balthasar Hubmaier, der Vorkämpfer fur Glaubens- und Gewissensfreiheit. Kassel, 1939.

Wiswedel, W. "Dr. Balthasar Hubmaier." Zeitschrift für bayerische Kirchengeschichte 15 (1940): 2 Halbbd. (reprint Gunzcnhausen, 1940).

Wolkan, Rudolf. Geschicht-Buch der Hutterischen Brüder. Macleod, AB, and Vienna, 1923.

Wolny, G. "Die Wiedertäufer in Mähren." Archiv für Österreichische Geschichte. (1850).

Windhorst, Christoph. Täuferisches Taufverständnis: Balthasar Hubmaiers Lehre Zwischen traditioneller und reformatorischer Theologie. Leiden: Brill, 1976.

| Author(s) | Johann Loserth |

|---|---|

| William R. Estep, Jr. | |

| Date Published | 1990 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Loserth, Johann and William R. Estep, Jr.. "Hubmaier, Balthasar (1480?-1528)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1990. Web. 16 Apr 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Hubmaier,_Balthasar_(1480%3F-1528)&oldid=103732.

APA style

Loserth, Johann and William R. Estep, Jr.. (1990). Hubmaier, Balthasar (1480?-1528). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 16 April 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Hubmaier,_Balthasar_(1480%3F-1528)&oldid=103732.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 826-834; vol. 5, p. 398. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.