Difference between revisions of "Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand (1869-1948)"

| [unchecked revision] | [checked revision] |

GameoAdmin (talk | contribs) (CSV import - 20130820) |

GameoAdmin (talk | contribs) (CSV import - 20130823) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

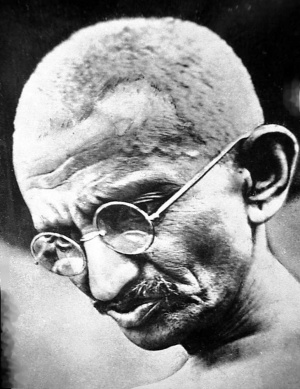

| − | [[File:Gandhi_portrait_1931.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Gandhi in 1931. WikiMedia Commons photo. | + | [[File:Gandhi_portrait_1931.jpg|300px|thumb|right|''Gandhi in 1931. WikiMedia Commons photo. '']] Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2 October 1869-30 January 1948) was a social reformer and political leader of [[India|India]] who led his compatriots in "nonviolent resistance" to secure for India independent statehood from the British Empire. Professionally trained as a barrister in England, he began his career in [[South Africa, Republic of|South Africa]] (1893-1914) where he encountered the grim realities of racial injustice. Here the spirit of the reformer was awakened and the foundations of his philosophy of nonviolent resistance were formulated. The term <em>Satyagraha </em>emerged as the term to describe and identify the essence of the movement. Two words, <em>satya </em>(truth) and <em>graha </em>(grasp) were joined to form <em>Satyagraha </em>meaning "holding on to truth." Motivated by the conviction that "truth" was on the side of the Indian claim for self-rule <em>(Swaraj) </em>he returned to India and allied himself with the independence movement. The "War without Violence" that ensued included active resistance and culminated in independent statehood by 1946. Three basic principles—"truth," "[[Nonviolence|nonviolence]]," and "self-suffering"—were to give direction to the forms of resistance and their implementation as the movement progressed. In his work, <em>War without Violence, </em>K. Shridharani classified the forms of resistance and graded them according to the level of coercion involved. These were identified as follows: "negotiation and arbitration," "agitation," "demonstration and ultimatum," "self-purification," "strike and general strike," "sit-down strike," "economic boycott," "civil disobedience," "assertive <em>Satyagraha," </em>"parallel government," "fasting," and "national defense." Procedurally it was the intent to clarify the facts of a given situation of injustice, whether in personal, labor and management, or political situations, and then to employ whatever nonviolent forms of action seemed appropriate. To reduce the hatred and malice that otherwise might infect the negotiation process, fasting and self-imposed halting of action were instituted. |

| − | |||

| − | '']] Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2 October 1869-30 January 1948) was a social reformer and political leader of [[India|India]] who led his compatriots in "nonviolent resistance" to secure for India independent statehood from the British Empire. Professionally trained as a barrister in England, he began his career in [[South Africa, Republic of|South Africa]] (1893-1914) where he encountered the grim realities of racial injustice. Here the spirit of the reformer was awakened and the foundations of his philosophy of nonviolent resistance were formulated. The term <em>Satyagraha </em>emerged as the term to describe and identify the essence of the movement. Two words, <em>satya </em>(truth) and <em>graha </em>(grasp) were joined to form <em>Satyagraha </em>meaning "holding on to truth." Motivated by the conviction that "truth" was on the side of the Indian claim for self-rule <em>(Swaraj) </em>he returned to India and allied himself with the independence movement. The "War without Violence" that ensued included active resistance and culminated in independent statehood by 1946. Three basic principles—"truth," "[[Nonviolence|nonviolence]]," and "self-suffering"—were to give direction to the forms of resistance and their implementation as the movement progressed. In his work, <em>War without Violence, </em>K. Shridharani classified the forms of resistance and graded them according to the level of coercion involved. These were identified as follows: "negotiation and arbitration," "agitation," "demonstration and ultimatum," "self-purification," "strike and general strike," "sit-down strike," "economic boycott," "civil disobedience," "assertive <em>Satyagraha," </em>"parallel government," "fasting," and "national defense." Procedurally it was the intent to clarify the facts of a given situation of injustice, whether in personal, labor and management, or political situations, and then to employ whatever nonviolent forms of action seemed appropriate. To reduce the hatred and malice that otherwise might infect the negotiation process, fasting and self-imposed halting of action were instituted. | ||

Mennonites in the search for alternatives to war and other forms of resistance to injustice have examined the Gandhian alternatives. Frequent references in Mennonite writings refer to and make comparison between "nonresistance" and "nonviolent resistance" or <em>Satyagraha. </em>Mennonite responses range all the way from rejection of the Gandhian forms of nonviolent resistance to at least some selective application in social and political situations. In <em>War, Peace and Nonresistance </em>Hershberger asserted "that non-resistant Christians cannot take part in a political [[Revolution|revolution]] for the overthrow of the government in power. But political revolution was Gandhi's primary objective. Gandhi's program was not one of nonresistance or peace. It was a new form of warfare" (pp 191-192). At the other end of the continuum would be the position expressed in the present writer's unpublished dissertation, "Some of the forms of <em>Satyagraha </em>which could conceivably he conducted in a manner consistent with the love-ethic are negotiations, arbitration, agitation, demonstration, strike, economic boycott, nonpayment of [[Taxes|taxes]], and noncooperation. Violence may enter into any one of these, but violence may enter into complete withdrawal in the form of hate. These modes of social action would represent love insofar as they retained emotional and physical discipline and were performed in the interest of a suffering minority (other than the one conducting the action), or in the interest of a principle of justice." (Groff, 212-13). As historically observed and documented the Gandhian movement did become violent and destructive at times. The course which he took by way of corrective was the self-purificatory fast and the cessation of <em>Satyagraha </em>activity. Inherent in both the principle of nonresistance and <em>Satyagraha </em>are self-regulatory criteria which test the rightness of the cause and the action employed. <em>"Satyagraha </em>is a principle of social action informing and controlling the conduct of social conflict, in which the end and the means thereto are consistent with the requirements of truth, nonviolence, and self-suffering. <em>Nonresistance </em>is the literal application to all relationships in society of the love-ethic of the New Testament. This is held to be the ethic of the spiritual kingdom to which the Christian owes prior loyalty. This loyalty in turn justifies abstention from those social and civil duties with which one cannot conscientiously comply; especially those that are not consistent with the divine moral law. The positive expression of the love-ethic (agape) is to 'overcome evil with good'." (ibid., 209). | Mennonites in the search for alternatives to war and other forms of resistance to injustice have examined the Gandhian alternatives. Frequent references in Mennonite writings refer to and make comparison between "nonresistance" and "nonviolent resistance" or <em>Satyagraha. </em>Mennonite responses range all the way from rejection of the Gandhian forms of nonviolent resistance to at least some selective application in social and political situations. In <em>War, Peace and Nonresistance </em>Hershberger asserted "that non-resistant Christians cannot take part in a political [[Revolution|revolution]] for the overthrow of the government in power. But political revolution was Gandhi's primary objective. Gandhi's program was not one of nonresistance or peace. It was a new form of warfare" (pp 191-192). At the other end of the continuum would be the position expressed in the present writer's unpublished dissertation, "Some of the forms of <em>Satyagraha </em>which could conceivably he conducted in a manner consistent with the love-ethic are negotiations, arbitration, agitation, demonstration, strike, economic boycott, nonpayment of [[Taxes|taxes]], and noncooperation. Violence may enter into any one of these, but violence may enter into complete withdrawal in the form of hate. These modes of social action would represent love insofar as they retained emotional and physical discipline and were performed in the interest of a suffering minority (other than the one conducting the action), or in the interest of a principle of justice." (Groff, 212-13). As historically observed and documented the Gandhian movement did become violent and destructive at times. The course which he took by way of corrective was the self-purificatory fast and the cessation of <em>Satyagraha </em>activity. Inherent in both the principle of nonresistance and <em>Satyagraha </em>are self-regulatory criteria which test the rightness of the cause and the action employed. <em>"Satyagraha </em>is a principle of social action informing and controlling the conduct of social conflict, in which the end and the means thereto are consistent with the requirements of truth, nonviolence, and self-suffering. <em>Nonresistance </em>is the literal application to all relationships in society of the love-ethic of the New Testament. This is held to be the ethic of the spiritual kingdom to which the Christian owes prior loyalty. This loyalty in turn justifies abstention from those social and civil duties with which one cannot conscientiously comply; especially those that are not consistent with the divine moral law. The positive expression of the love-ethic (agape) is to 'overcome evil with good'." (ibid., 209). | ||

Revision as of 14:02, 23 August 2013

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2 October 1869-30 January 1948) was a social reformer and political leader of India who led his compatriots in "nonviolent resistance" to secure for India independent statehood from the British Empire. Professionally trained as a barrister in England, he began his career in South Africa (1893-1914) where he encountered the grim realities of racial injustice. Here the spirit of the reformer was awakened and the foundations of his philosophy of nonviolent resistance were formulated. The term Satyagraha emerged as the term to describe and identify the essence of the movement. Two words, satya (truth) and graha (grasp) were joined to form Satyagraha meaning "holding on to truth." Motivated by the conviction that "truth" was on the side of the Indian claim for self-rule (Swaraj) he returned to India and allied himself with the independence movement. The "War without Violence" that ensued included active resistance and culminated in independent statehood by 1946. Three basic principles—"truth," "nonviolence," and "self-suffering"—were to give direction to the forms of resistance and their implementation as the movement progressed. In his work, War without Violence, K. Shridharani classified the forms of resistance and graded them according to the level of coercion involved. These were identified as follows: "negotiation and arbitration," "agitation," "demonstration and ultimatum," "self-purification," "strike and general strike," "sit-down strike," "economic boycott," "civil disobedience," "assertive Satyagraha," "parallel government," "fasting," and "national defense." Procedurally it was the intent to clarify the facts of a given situation of injustice, whether in personal, labor and management, or political situations, and then to employ whatever nonviolent forms of action seemed appropriate. To reduce the hatred and malice that otherwise might infect the negotiation process, fasting and self-imposed halting of action were instituted.

Mennonites in the search for alternatives to war and other forms of resistance to injustice have examined the Gandhian alternatives. Frequent references in Mennonite writings refer to and make comparison between "nonresistance" and "nonviolent resistance" or Satyagraha. Mennonite responses range all the way from rejection of the Gandhian forms of nonviolent resistance to at least some selective application in social and political situations. In War, Peace and Nonresistance Hershberger asserted "that non-resistant Christians cannot take part in a political revolution for the overthrow of the government in power. But political revolution was Gandhi's primary objective. Gandhi's program was not one of nonresistance or peace. It was a new form of warfare" (pp 191-192). At the other end of the continuum would be the position expressed in the present writer's unpublished dissertation, "Some of the forms of Satyagraha which could conceivably he conducted in a manner consistent with the love-ethic are negotiations, arbitration, agitation, demonstration, strike, economic boycott, nonpayment of taxes, and noncooperation. Violence may enter into any one of these, but violence may enter into complete withdrawal in the form of hate. These modes of social action would represent love insofar as they retained emotional and physical discipline and were performed in the interest of a suffering minority (other than the one conducting the action), or in the interest of a principle of justice." (Groff, 212-13). As historically observed and documented the Gandhian movement did become violent and destructive at times. The course which he took by way of corrective was the self-purificatory fast and the cessation of Satyagraha activity. Inherent in both the principle of nonresistance and Satyagraha are self-regulatory criteria which test the rightness of the cause and the action employed. "Satyagraha is a principle of social action informing and controlling the conduct of social conflict, in which the end and the means thereto are consistent with the requirements of truth, nonviolence, and self-suffering. Nonresistance is the literal application to all relationships in society of the love-ethic of the New Testament. This is held to be the ethic of the spiritual kingdom to which the Christian owes prior loyalty. This loyalty in turn justifies abstention from those social and civil duties with which one cannot conscientiously comply; especially those that are not consistent with the divine moral law. The positive expression of the love-ethic (agape) is to 'overcome evil with good'." (ibid., 209).

Though Gandhi was known more popularly because of his involvement with the independence movement, his energies were also devoted to education and to economic and social betterment for the poor, especially the "outcastes," of India. He gave these persons the dignity of the name Harijan meaning children of God. This broader program of social service and experimentation came under the umbrella term Sarvodaya (welfare of all). Within this program was a scheme of basic education aimed at improving conditions for the masses of Indian people who lived in villages; particularly as it would enable them to be more self-sufficient by producing their own cloth, soap, etc.

Following independence and the partition of India and Pakistan, riots created turmoil and heavy loss of life for both Hindus and Muslims. Gandhi invested himself in an exhausting series of efforts to bring about reconciliation but was killed by an assassin's bullet.

In 1983 a highly-acclaimed commercial film, Gandhi, produced in Great Britain and directed by Richard Attenborough, brought the story of Gandhi to the attention of a later generation.

Bibliography

Groff, Weyburn W. "Nonviolence: A Comparative Study of Mohandas K. Gandhi and the Mennonite Church on the Subject of Nonviolence." PhD dissertation, New York University, 1963.

Hershberger, Guy F. War, Peace and Nonresistance. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1953.

Kauffman, Ralph C. "Satyagraha and Christian Pactfism." The Mennonite (21 February 1946): 3-6.

Nanda, Bal. R. Mahatma Gandhi. Boston: Beacon Press, 1958.

Shridharani, Krishnalal J. War Without Violence. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1939.

Juhnke, James C. A People of Mission: A History of General Conference Mennonite Overseas Missions. Newton, KS: Faith and Life, 1979: 43, 103, 165.

Lapp, John Allen. The Mennonite Church in India, 1897-1962, Studies in Anabaptist and Mennonite History, vol. 14. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1972: 82-83, 88-93.

Shelly, Griselda Gehman. "A Letter from Mahatma Gandhi." Mennonite Life 38 (June 1983): 25-27;

Mennonite Life 25 (October 1970): 155-159.

| Author(s) | Weyburn W Groff |

|---|---|

| Date Published | 1987 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Groff, Weyburn W. "Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand (1869-1948)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1987. Web. 16 Apr 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Gandhi,_Mohandas_Karamchand_(1869-1948)&oldid=91848.

APA style

Groff, Weyburn W. (1987). Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand (1869-1948). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 16 April 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Gandhi,_Mohandas_Karamchand_(1869-1948)&oldid=91848.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 5, pp. 323-324. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.