Difference between revisions of "Friesland (Netherlands)"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (Text replace - "</em><em>" to "") |

m (Text replace - "<em>Mennonitisches Lexikon</em>" to "''Mennonitisches Lexikon''") |

||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

Buse, H. J. <em>De verdwenen Doopsgezinde Gemeenten in Friesland. </em>Reprint from <em>De Frije Fries </em>22. | Buse, H. J. <em>De verdwenen Doopsgezinde Gemeenten in Friesland. </em>Reprint from <em>De Frije Fries </em>22. | ||

| − | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. | + | Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. ''Mennonitisches Lexikon'', 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: vol. II, 9-12. |

Kühler, Wilhelmus Johannes. <em>Geschiedenis der Nederlandsche Doopsgezinden in de Zestiende Eeuw</em>. Haarlem: H.D. Tjeenk Willink, 1932. | Kühler, Wilhelmus Johannes. <em>Geschiedenis der Nederlandsche Doopsgezinden in de Zestiende Eeuw</em>. Haarlem: H.D. Tjeenk Willink, 1932. | ||

Revision as of 07:28, 16 January 2017

Introduction

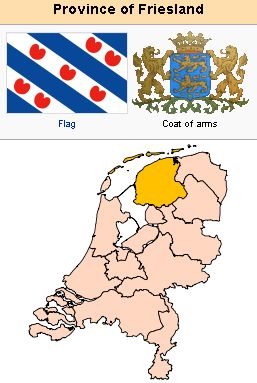

Friesland (West Frisian, Fryslân), a province in the North of the Netherlands (area 1,431 sq. miles, 1949 pop. 464,450; 13,328 Mennonites or nearly 3 per cent; 2005 pop. 643,000). In Friesland there are no big cities; the largest are the capital, Leeuwarden (1949 pop. 77,000; 2005 pop. 84,000) and Sneek (1949 pop. 19,000; 2006 pop. 33,000). In the 1950s there was not much industry in Friesland, farming being its principal means of support. The center of the province is below sea level, protected from the water and divided into polders by dikes; in this part there are still a number of lakes. In the summer Sneek and Grouw were centers of aquatic sports. The southeast part of the province is the less fertile. Very few Mennonites live here. In the north agriculture predominated (potatoes, especially seed potatoes for export, wheat, flax; intensive gardening in the Bildt district). The west and southwest part was excusively used for dairy farming and cattle breeding. Cattle breeding was at a high level in the 1950s; most cows, of the black-and-white Frisian breed, were registered. Cows and bulls were exported to all parts of the world. The Leeuwarden Friday cattle market was one of the largest of Europe (highest sale 10,000 head). Of great importance was the production of milk (770,000 tons per annum in the 1950s); hence there was a considerable export of butter. There were 98 dairy processing plants, most of them large; 78 of them were cooperative enterprises. Since 1932, when the Zuiderzee (now IJsselmeer) was closed in by a dike, the fishing industry, formerly of importance at Staveren, Makkum, and other seacoast towns, had largely declined. To the province of Friesland also belonged the North Sea islands of Schiermonnikoog, Ameland, and Terschelling.

Friesland has its own language, quite different from the Dutch and closely related to Old English. The Frisian language was still the common language in Friesland in the mid-20th century, at least in the country. In church services, however, the Dutch language was generally used, but services in the Frisian language were occasionally held. There is a Frisian translation of the Bible.

Mennonites in Friesland

In 1954 there were 46 Mennonite congregations in Friesland and 9 fellowship groups (Kring) in towns where there was no organized Mennonite church. All congregations were organized into one conference, the Sociëteit van Doopsgezinde Gemeenten in Friesland. The youth groups of the several congregations are organized in the Friese Doopsgezinde Jongerenbond (F.D.J.B.) and the Ladies' Circles also in a general confederation, meeting regularly at Leeuwarden. For the practical purpose of assisting each other in cases of pulpit vacancy, the congregations were organized into three groups of district conferences called Ring, viz., Dantumawoude, Akkrum, and Bolsward.

History

As to Anabaptism and Mennonitism Friesland occupies a prominent place among the Dutch provinces. Anabaptism was found here as early as 1530 and nowhere in the Netherlands was Mennonitism as deeply rooted in the population as here. About 1530 a circle of peaceful Melchiorites arose at Leeuwarden, probably through the preaching of Melchior Hoffman. In 1531 Sicke Freerks, a tailor, was beheaded in Leeuwarden. It was this martyrdom that caused Menno Simons, who was a priest at Witmarsum, a village near Leeuwarden, to become interested in a study of the question of infant baptism, which doctrine he consequently rejected as un-Biblical. Here, too, Münsterite Anabaptism caused some confusion; Jan van Geelen distributed the noted booklet Van der Wraeke, and as a result a group of revolutionary Anabaptists in the spring of 1535 seized the Oldekloster near Bolsward. A week later it was retaken by the Stadholder of Friesland. In this disturbance a brother of Menno Simons lost his life. About 50 prisoners were taken and executed at Leeuwarden.

Menno then wrote his booklet Against the Blasphemy of Jan van Leiden, and in January 1536 withdrew from the Catholic Church. The leader of the Anabaptists at that time was Obbe Philips in Leeuwarden. Early in 1537 he ordained Menno, who was then living in a quiet village in Groningen, as elder. Menno for some time traveled about Friesland, preaching and baptizing, but fled to Germany with Obbe Philips when the authorities put a price upon his head. Another preacher, Frans de Kuiper, was arrested at Leeuwarden, but was released upon recanting and betraying a number of his brethren. By 1575 about 50 Anabaptists had been seized and executed, of the many who lived here. Soon after 1550 the influx of Anabaptist refugees from Flanders, where severe persecution had set in, to the Netherlands began. Some of these refugees settled in Friesland. Most of these new members were baptized by Leenaert Bouwens, who fearlessly made repeated journeys through Friesland. It was about this time, after Menno Simons had sided with the strict party of Dirk Philips and Leenaert Bouwens at the conference in Harlingen in 1555, that the four important congregations, Leeuwarden, Dokkum, Sneek, and Harlingen, formed a union, and chose Ebbe Pieters of Harlingen as their elder. Pieters was, however, unable to travel over the province to administer baptism, and since Menno Simons had died and Leenaert Bouwens had been suspended from his office as elder, baptism was for a while not performed. Thereupon the Flemish in 1565 chose Jeroen Tinnegiteter as their preacher.

This led to great disunity, because Ebbe was so ambitious to secure this election, and the brotherhood throughout the country was divided into two parties, the Flemish and the Frisians. About 1588 a new conflict arose among the Flemish over the purchase of a house that was to serve as a church, causing a division into Huiskoopers or Old Flemish, and Contra-Huiskopers. The Frisians also divided into the "Hard" and "Soft" Frisians. Besides these divisions, further schisms resulted in the groups known as the Waterlanders, Jan-Jacobsgezinden, Pieter-Jeltjesvolk, and others. The consequence was that in the small villages there were usually two or more congregations side by side. But most of these groups were reunited in the course of the 17th century. The last union took place at Oldeboorn in the 19th century.

After the period of persecution was past, the Mennonites of Friesland, as indeed in all of the Netherlands, were scarcely tolerated. Nevertheless with few exceptions the situation of the Mennonites in Friesland was generally satisfactory, especially after the close of the 17th century. In return for a contribution (compulsory, to be sure) of 1,032,943 guilders in 1672-1676 for the equipment of the Frisian navy flotilla, they were officially released from the oath and military service. For the benefit of their orphanages and their care of the poor they were excused from taxes on flour, meat, beer, and peat. By 1673 the Mennonites of Friesland had been given certain political rights, such as joining with the Reformed citizens in electing the representatives in the regional Frisian government, and were called "Lovers of the true Reformed Religion." Nevertheless there was not yet real toleration; even in the following century the edict (placaat) against the Socinians, Quakers, and Dompelaars (1662) was still in force, and in the first decades of the 18th century the Mennonites were often opposed on the basis of this regulation. In 1683 the preacher Foecke Floris was expelled from the province; in 1719 Jan Thomas, a preacher at Heerenveen, was suspended from his ministry by the government of Friesland, and upon the request of the Reformed Synod in 1722 the government passed an edict compelling all Mennonite preachers to sign a formulary of faith prescribed by the Reformed Church. Since all of the 150 Mennonite preachers of the time with the exception of one (Meint Cuyper of Grouw) refused to sign, all the Mennonite churches were closed; and a month later the requirement was withdrawn. In 1738 two Mennonite preachers of Heerenveen were dismissed from their office (see Pieke Tjommes), and Joannes Stinstra, preacher at Harlingen and chairman of the Frisian Societeit, was forbidden to preach 1742-1757. Not until 1795 were the Mennonites given equal rights with the Reformed.

The violent quarrels at the end of the 16th century resulted in a large number of Mennonites uniting with the Reformed Church. The War of Liberation against the Spanish also contributed to this transfer of membership. Most of the Mennonites, with the exception of the cities in the north and west, were living along the seacoast and the canals. In the southeast the congregations were less numerous. The institution of the lay (untrained) ministry in the congregations also had an adverse effect on the numerical growth.

In the second half of the 17th century the Dutch Mennonites were split into the Zonists and the Lamists through the influence of the liberal Galenus Abrahamsz and the more liberal Socinians. But this division was less serious in Friesland, where a provincial conference was organized in 1695, the Societeit van Doopsgezinde Gemeenten in Friesland, which was a great blessing throughout the 18th century—the age of decline, in which Friesland lost no fewer than 22 congregations—in its striving to hold the church together as much as possible and to aid the poorer congregations in supporting a preacher. The Societeit organized a fund for the support of ministers, a fund for retired ministers, and a fund for the support of widows of ministers, to which all the congregations of Friesland belong. A fund for the increase of ministerial salaries was founded in 1865, and a fund (Studiefonds) for the education of ministers in 1857.

A new "golden age" came when after the French occupation the Algemene Doopsgezinde Sociëteit was established and gradually led to the employment of trained ministers in all the congregations. In the second half of this century nearly all the congregations acquired modernist preachers. Not until the mid-20th century was this situation changed to some extent, a number of congregations in Friesland calling younger, more orthodox ministers. Bovenknijpe in Friesland was the first Dutch congregation to engage a woman as minister: in 1911 Miss Annie Mankes, later Mrs. A. Mankes-Zernika, accepted this office. The congregation at Dokkum has for over 150 years been united with the Remonstrant congregation, but it is nevertheless a member of the Mennonite Ring.

The membership of the Mennonite congregations in Friesland has dropped appreciably since the 17th century, particularly in relation to the population increase. In 1666 there were 4,856 baptized male members, indicating a probable total of 20,000 souls, or 22 per cent of the total population. In 1838 there were 12,870 souls, or about 5 per cent, and in 1949, 13,328, or 3 per cent.

In the 19th century a number of new congregations arose: Appelscha, which was soon dissolved, and the following congregations which were still in existence in 1954; St-Anna-Parochie, Koudum, Ternaard, Tjalleberd, and Wolvega. In the 20th century Zwaagwesteinde was added, as well as the fellowship groups (Kring): Bergum, Giekerk, Kollum-Buitenpost, Langweer, Oosterwolde, Oranjewoud, Stiens, Twijzel-Eestrum, and Vrouwenparochie.

Table

The following list gives a survey of the distribution of the baptized members in the various congregations in Friesland:

| Congregation | 1883 | 1885 | 1923 | 1956 |

| Akkrum | 321 | 408 | 370 | 181 |

| Ameland1 | 320 | 290 | 225 | 197 |

| Sint Anna-Parochie | - | 65 | 170 | 133 |

| Baard | 86 | 115 | 90 | 51 |

| Balk | 35 | 91 | 72 | 85 |

| Berlikum | 12 | 72 | 89 | 151 |

| Bolsward | 157 | 216 | 208 | 120 |

| Bovenknijpe | 123 | 231 | 145 | 94 |

| Dantumawoude | 207 | 263 | 220 | 212 |

| Drachten-Ureterp | 183 | 278 | 220 | 120 |

| Franeker | 95 | 1162 | 175 | 120 |

| Gorredijk-Lippenhuizen | 118 | 195 | 150 | 155 |

| Grouw | 275 | 433 | 345 | 206 |

| Hallum | 20 | 40 | 125 | 155 |

| Harlingen | 272 | 514 | 400 | 351 |

| Heerenveen | 144 | 286 | 229 | 209 |

| Hindeloopen | 57 | 32 | 65 | 48 |

| Holwerd-Blija | 165 | 268 | 140 | 92 |

| IJlst | 135 | 104 | 75 | 84 |

| Irnsum | 87 | 112 | 135 | 102 |

| Itens | 65 | 112 | 100 | 98 |

| Joure | 200 | 358 | 350 | 230 |

| Koudum | - | 35 | 40 | 26 |

| Leeuwarden | 270 | 782 | 1350 | 1020 |

| Makkum | 90 | 97 | 78 | 48 |

| Molkwerum3 | 20 | 29 | 47 | - |

| Oldeboorn4 | 288 | 521 | 338 | 182 |

| Oude Bildtzijl | 34 | 71 | 125 | 143 |

| Poppingawier | - | 80 | 65 | 45 |

| Rottevalle-Witween | 72 | 112 | 128 | 142 |

| Sneek | 310 | 444 | 460 | 465 |

| Staveren | 25 | 47 | 68 | 56 |

| Surhuisterveen | 68 | 70 | 105 | 134 |

| Terhorne | 119 | 135 | 100 | 85 |

| Ternaard | - | 66 | 80 | 101 |

| Terschelling | 1315 | 1546 | 1407 | 144 |

| Tjalleberd | 104 | 132 | 115 | 103 |

| Veenwouden | 36 | 83 | 155 | 195 |

| Warga | 159 | 192 | 166 | 91 |

| Warns | 108 | 131 | 106 | 110 |

| Witmarsum/Pingjum | 50 | 85 | 70 | 54 |

| Wolvega | - | 61 | 80 | 101 |

| Workum | 74 | 81 | 105 | 94 |

| Woudsend | 34 | 32 | 38 | 34 |

| Zwaagwesteinde | 3 | ? | 75 | 88 |

| Total | 5072 | 8039 | 8217 | 6779 |

| 1 The congregations of Ballum, Hollum, and Nes.

2In 1895. 3 Merged with Warns in 19—. 4 Divided into two congregations in 1838. 5 In 1847. 6 In 1897. 7 Until 1942 Terschelling belonged to the province of North Holland. | ||||

Bibliography

Cate, Steven Blaupot ten. Geschiedenis der Doopsgezinden in Friesland. Leeuwarden: W. Eekhoff, 1839.

Buse, H. J. De verdwenen Doopsgezinde Gemeenten in Friesland. Reprint from De Frije Fries 22.

Hege, Christian and Christian Neff. Mennonitisches Lexikon, 4 vols. Frankfurt & Weierhof: Hege; Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913-1967: vol. II, 9-12.

Kühler, Wilhelmus Johannes. Geschiedenis der Nederlandsche Doopsgezinden in de Zestiende Eeuw. Haarlem: H.D. Tjeenk Willink, 1932.

Kühler, Wilhelmus Johannes. Geschiedenis van de Doopsgezinden in Nederland II. 1600-1735 Eerste Helft. Haarlem: H.D. Tjeenk Willink & Zoon n.v., 1940.

Kühler, Wilhelmus Johannes. Geschiedenis van de Doopsgezinden in Nederland: Gemeentelijk Leven 1650-1735. Haarlem: H.D. Tjeenk Willink & Zoon, 1950.

Pasma, F. H. De Friese Doopsgezinde Gemeenten in de lautste halve eeuw. N.p., n.d., 1947.

Zijpp, N. van der. Geschiedenis der Doopsgezinden in Nederland. Arnhem, 1952.

Detailed information is found in the articles on individual congregations.

| Author(s) | Karel Vos |

|---|---|

| Nanne van der Zijpp | |

| Date Published | 1956 |

Cite This Article

MLA style

Vos, Karel and Nanne van der Zijpp. "Friesland (Netherlands)." Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1956. Web. 16 Apr 2024. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Friesland_(Netherlands)&oldid=146436.

APA style

Vos, Karel and Nanne van der Zijpp. (1956). Friesland (Netherlands). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 16 April 2024, from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Friesland_(Netherlands)&oldid=146436.

Adapted by permission of Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia, from Mennonite Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, pp. 407-410. All rights reserved.

©1996-2024 by the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. All rights reserved.